In 2018, implicit racial bias research in education continued its expanded attention to the impact of implicit biases on students and education policy. Our review includes nine (9) studies published in 2018. Ranging from how educators’ unconscious stereotypes may lead to the dehumanization and marginalization of youth of color, to disparities in disciplinary actions and evaluations of learning skills, these studies provide an in-depth look at the pervasiveness of implicit bias in educational settings.

In educational settings, implicit bias has been well-documented in the literature as a contributing factor to differences in teacher-student interactions (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015; Warikoo et al., 2016). Beyond the classroom, however, implicit racial biases potentially held by school administrators, such as principals and vice principals who are also an integral part of education systems, are rarely examined. The impacts of implicit racial biases manifest students’ mental/behavioral/health and academic outcomes, as well as aggregated racial disparities in school discipline and underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minoritized populations across various academic fields. Understanding these biases, their manifestations, and impacts, can expand our ability to creatively address the persistent challenges implicit biases present in educational contexts.

Impact on Students

According to new research published in 2018, the detrimental effects of implicit racial biases on students can be classified into two subcategories: societal and institutional devaluation and negative academic outcomes. We take each in turn.

Prior research documents the ways in which implicit bias may lead to a dehumanization process where youth of color are perceived as older, less innocent, and therefore more accountable for their actions than their White peers of the same age (Goff et al., 2014). This dehumanization process could result in reduced or absent social protection in school settings, making children of color more susceptible to punitive measures and less likely to be given chances to rectify their wrongdoings (Goff et al., 2008). Building on the earlier work of Philip Goff (2008; 2014); Matteo Forgiarini and colleagues (2011); Joshua Correll and colleagues (2002); and Walter Gilliam and colleagues (2016), Annamma and Morrison (2018) argued that young individuals of color are subjected to the negative impacts of implicit bias through dehumanization, pain minimization, and fear maximization. Citing empirical evidence, Annamma and Morrison detailed in their discussion the process by which youth of color as young as 12-years old are dehumanized while their pain may be overlooked. The outcomes can be fatal for some, as seen in the case of Tamir Rice, who was shot by Cleveland police while playing with a toy gun. Meanwhile, others may endure less direct but still damaging forms of violence by adults in authority.

The role of fear maximization and dehumanization also affects subgroups of the United States population in particular ways. Anthony Brown (2018) offered a thorough review of theological, scientific, and social science discourses where the construction of race has been shaped in relation to Black males. The impact of these biased practices, according to Brown, originates from the durable racial discourses of power that persistently portray Black males as feared and dangerous. In this way Brown also emphasizes the connections between fear maximization, dehumanization, and implicit racial bias against Black males in schools and society.

A second area of 2018 research focuses on the impact of implicit racial biases upon teachers’ evaluations of students’ learning skills. Building on the prior work of Lennard Davis’s critical disability theory (2013), Parekh and colleagues (2018) argued that it is important to examine the role of implicit racial bias in teachers’ evaluations of students’ learning skills and how it affects different communities. They suggested that critical disability theory is particularly relevant because it dissects how our society’s excessive emphasis on ability can unfairly label people, especially those from communities that often struggle with poverty and precarity. Their exploratory study of teachers’ perception of students’ learning skills across demographic and institutional factors drew data from Canada’s largest public board of education, which served approximately 246,000 students at the time of the study. The researchers examined the associations between students’ self-reported racial identity and the degree to which they were noted as having “Excellent” learning skills across achievement categories. The findings indicated that White students were typically the most likely to be given this high rating for their learning skills. On the other hand, despite being compared at similar academic levels, students self-identifying as Black were less likely to be recognized as having “Excellent” learning skills. The results imply that Black students, irrespective of their academic performance, are not perceived to embody core attributes implicitly valued by the educational system.

This 2018 study aligns with similar results found at the post-secondary level in earlier research. In a simulated setting that replicated teaching interactions involving college student participants who exhibited lower performance on a test, researchers discovered that White instructors showed stronger implicit associations favoring White individuals and harbored negative associations towards similarly situated Black individuals (Jacoby-Senghor et al., 2015). Another study examined implicit racial associations held by teachers concerning White and Arab individuals in the United States (Kumar et al., 2015). It was observed that teachers with implicit biases favoring White individuals and holding negative associations towards Arab individuals were less inclined to establish a culturally responsive classroom environment and facilitate the resolution of interethnic conflicts within the classroom.

Historically both the intention and assumption of the roles that teachers play in classrooms have been focused on teachers’ ability to promote egalitarian attitudes and foster harmony among individuals of different races. Teachers – particularly but not exclusively White teachers – have been found to play a significant role in perpetuating racial inequality that requires attention, intention, and mitigation (Ladson-Billings, 1994; Gershenson et al. 2016). Please see the Mitigation Strategies section of this report for research findings regarding successful interventions.

Systemic Impact

Having explored the intricate ways in which implicit bias can directly impact student outcomes, we now investigate how these biases further manifest in specific areas of the educational system. In the education sector, the role of implicit bias has been linked to racial disparities in school disciplinary actions. Racial disparities play a significant role in both K-12 educational outcomes like high school graduation rates and youth getting caught up in what is now commonly called the “school-to-prison pipeline.” The stakes, therefore, could not be higher for young people.

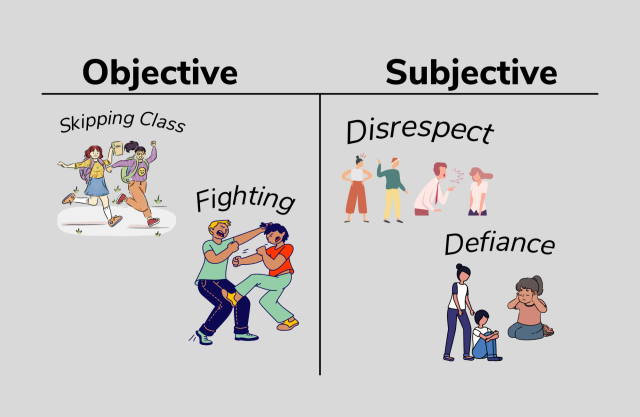

The first area of systemic implicit racial biases’ impact is school discipline. A vast amount of prior research suggests that disciplinary methods in schools affect students of color more than their peers (such as Wallace et al., 2008; Skiba et al., 2011; Hannon et al., 2013). A plethora of studies have found that certain student subgroups face a disproportionate amount of exclusionary discipline (Aud et al., 2011; Nowicki, 2018; U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2015). Implicit racial bias is one of the contributing factors to this problem (Girvan et al., 2017; Goff et al., 2014), particularly under certain conditions, such as when teachers or administrators are making decisions that are ambiguous, demand fast judgement, or when they are physically or mentally drained (Kouchaki & Smith, 2014). Black students were found to be significantly more likely than White students to be labeled as troublemakers, their misbehaviors were more likely to be perceived as indicative of a pattern. Educators also showed a higher tendency to envision themselves suspending a Black student in the future compared to a White student. (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015). The role of implicit bias in school discipline becomes more evident when we examine the disparities for more subjective behavior infractions such as disruption, as opposed to objective infractions like theft (Skiba et al., 2011). Objective infractions are behaviorally defined and based on objective event (e.g., fighting, skipping classes) that often leaves a permanent product, whereas subjective infractions are defined vaguely and more open to subjective interpretation (e.g., defiance, disrespect; Skiba et al., 2002; Theriot & Dupper, 2010). A study of student discipline records from more than 1,800 schools unveiled that these disparities were largely due to racial differences in office discipline referrals for subjectively defined behaviors such as defiance (Girvan et al., 2017). In sum, the past 12 years of studies reveal a troubling trend of systemic unfair treatment of students of color attributable to implicit racial bias.

A second area of systemic implicit racial biases’ impact is the persistent underrepresentation of racially minority students in particular fields, including but not limited to STEM education (McGee, 2021). Two 2018 studies – one in chemical engineering and one in the humanities – explored this impact, as did a cross-disciplinary study of recommendation letters. Farrell and Minerick (2018) examined the stealth nature of implicit bias in the realm of chemical engineering education. They argued that the pervasive presence of implicit bias and stereotype threat creates an environment where educators tend to allocate their time and resources to those students they perceive as more likely to succeed. Such an environment is likely to generate self-fulfilling prophecies and to negatively impact students’ interest in a subject as well as their levels of effort. In the same vein, Holroyd and Saul (2018) provided a detailed discussion of implicit bias in the field of philosophy. The authors suggested that implicit biases might be part of the explanation for the persisting underrepresentation and marginalization of multiple groups in philosophy. For instance, Black PhD students and professional philosophers combined are merely 1.32% of philosophers in the U.S. (Botts et al., 2014). The authors further emphasized the gravity of the situation, noting how implicit biases perpetuate unjust societal structures.

The role of implicit bias is not only limited to direct interactions between educators and students, but it also permeates more indirect aspects of the education system such as recommendation letters. Letters of recommendation, often utilized to evaluate undergraduate students’ potential for success as research assistants, interns, or graduate students, can sometimes include implicit bias, thereby potentially impacting decisions and constraining opportunities for underrepresented minorities and students from non-research institutions. Houser and Lemmons (2018) employed a text analysis software to analyze 457 recommendation letters for undergraduates applying for an international research experience, aiming to identify any significant difference in the language used to depict students who were accepted versus those who were rejected. The findings indicate that recommendation letters for successful applicants depict the students’ productivity with more certainty and incorporate more student work quotes. Conversely, the letters for unsuccessful applicants contain more positive emotion and mention the students’ insight, but also include more discrepancy-associated words (e.g., should) and tentative statements (e.g., perhaps, maybe). The statistically significant results showed the White students tended to be described in relation to their cognitive ability, insightfulness, productivity, and perceptiveness while non-White students tended to be depicted in affective languages and positive emotions.

Taken together, research conducted in 2018 regarding the impact of implicit bias continues to document the deleterious effects of implicit racial bias on students of color as well as an aggregate impact that produces systemic racial disparities. Highlights from 2018 include a theoretical focus on the mechanisms of dehumanization and fear maximization directed at individuals of color. This was complemented by studies that explored the role of implicit bias in teachers’ evaluation, nuances in recommendation letters, and underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority populations across various academic fields. These studies and critical analyses provide a more updated understanding of the scope of implicit racial bias in education, underscoring the urgency for the sector to take meaningful actions.