Xiaodan Hu, PhD & Ange-Marie Hancock, PhD | Published 03:00 p.m. ET May 22, 2024.

Cite this article (APA-7): Hu, X., & Hancock, A. M. (2024). State of the science: Implicit Bias in Education 2018-2020. The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. https://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/state-science-implicit-bias-education-2018-2020

Introduction

Over the past 10 years, the Kirwan Institute has explored developments in implicit bias research in education. Schools are oftentimes believed to have the power in promoting more positive racial attitudes and allowing all to partake equitably in society (e.g., Banks et al., 2006). However, teachers and school administrators who are entrusted with fulfilling this capacity, are themselves immersed in a social environment where implicit racial biases are pervasive (Nosek et al., 2007; Gullo & Beachum, 2020). For this multi-year State of the Science report, we examined 33 articles published between 2018-2020 that interrogated the role of implicit racial bias in education

Our earliest State of the Science report (Staats & Patton, 2013) identified teacher-student interactions, evaluations of student performance and teachers’ expectations of students as key areas of research. Following a drop in the number of publications in this research area, an outcome lamented by scholars cited in our 2014 report (Staats, 2014), the 2015 State of the Science (Staats et al., 2015) broadened the scope of review for implicit racial bias research in education to include manifestations of implicit racial bias among students themselves. This added a new dimension to the existing discussion, implying that implicit bias in education is not just an issue among educators but also emerges in students as they age. The reports from 2016 and 2017 (Staats et al., 2016; Staats et al., 2017) documented the expansion of research involving teachers and students across different grade levels (students) and different career stages (teachers). One key takeaway from 10 years of these reviews is the persistent impact of implicit biases in educational settings.

Implicit Bias in Education: 2018

In 2018, implicit racial bias research in education continued its expanded attention to the impact of implicit biases on students and education policy. Our review includes nine (9) studies published in 2018. Ranging from how educators' unconscious stereotypes may lead to the dehumanization and marginalization of youth of color, to disparities in disciplinary actions and evaluations of learning skills, these studies provide an in-depth look at the pervasiveness of implicit bias in educational settings.

In educational settings, implicit bias has been well-documented in the literature as a contributing factor to differences in teacher-student interactions (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015; Warikoo et al., 2016). Beyond the classroom, however, implicit racial biases potentially held by school administrators, such as principals and vice principals who are also an integral part of education systems, are rarely examined. The impacts of implicit racial biases manifest students’ mental/behavioral/health and academic outcomes, as well as aggregated racial disparities in school discipline and underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minoritized populations across various academic fields. Understanding these biases, their manifestations, and impacts, can expand our ability to creatively address the persistent challenges implicit biases present in educational contexts.

Impact on Students

According to new research published in 2018, the detrimental effects of implicit racial biases on students can be classified into two subcategories: societal and institutional devaluation and negative academic outcomes. We take each in turn.

Prior research documents the ways in which implicit bias may lead to a dehumanization process where youth of color are perceived as older, less innocent, and therefore more accountable for their actions than their White peers of the same age (Goff et al., 2014). This dehumanization process could result in reduced or absent social protection in school settings, making children of color more susceptible to punitive measures and less likely to be given chances to rectify their wrongdoings (Goff et al., 2008). Building on the earlier work of Philip Goff (2008; 2014); Matteo Forgiarini and colleagues (2011); Joshua Correll and colleagues (2002); and Walter Gilliam and colleagues (2016), Annamma and Morrison (2018) argued that young individuals of color are subjected to the negative impacts of implicit bias through dehumanization, pain minimization, and fear maximization. Citing empirical evidence, Annamma and Morrison detailed in their discussion the process by which youth of color as young as 12-years old are dehumanized while their pain may be overlooked. The outcomes can be fatal for some, as seen in the case of Tamir Rice, who was shot by Cleveland police while playing with a toy gun. Meanwhile, others may endure less direct but still damaging forms of violence by adults in authority.

The role of fear maximization and dehumanization also affects subgroups of the United States population in particular ways. Anthony Brown (2018) offered a thorough review of theological, scientific, and social science discourses where the construction of race has been shaped in relation to Black males. The impact of these biased practices, according to Brown, originates from the durable racial discourses of power that persistently portray Black males as feared and dangerous. In this way Brown also emphasizes the connections between fear maximization, dehumanization, and implicit racial bias against Black males in schools and society.

A second area of 2018 research focuses on the impact of implicit racial biases upon teachers’ evaluations of students’ learning skills. Building on the prior work of Lennard Davis’s critical disability theory (2013), Parekh and colleagues (2018) argued that it is important to examine the role of implicit racial bias in teachers’ evaluations of students’ learning skills and how it affects different communities. They suggested that critical disability theory is particularly relevant because it dissects how our society’s excessive emphasis on ability can unfairly label people, especially those from communities that often struggle with poverty and precarity. Their exploratory study of teachers’ perception of students’ learning skills across demographic and institutional factors drew data from Canada’s largest public board of education, which served approximately 246,000 students at the time of the study. The researchers examined the associations between students’ self-reported racial identity and the degree to which they were noted as having “Excellent” learning skills across achievement categories. The findings indicated that White students were typically the most likely to be given this high rating for their learning skills. On the other hand, despite being compared at similar academic levels, students self-identifying as Black were less likely to be recognized as having "Excellent" learning skills. The results imply that Black students, irrespective of their academic performance, are not perceived to embody core attributes implicitly valued by the educational system.

This 2018 study aligns with similar results found at the post-secondary level in earlier research. In a simulated setting that replicated teaching interactions involving college student participants who exhibited lower performance on a test, researchers discovered that White instructors showed stronger implicit associations favoring White individuals and harbored negative associations towards similarly situated Black individuals (Jacoby-Senghor et al., 2015). Another study examined implicit racial associations held by teachers concerning White and Arab individuals in the United States (Kumar et al., 2015). It was observed that teachers with implicit biases favoring White individuals and holding negative associations towards Arab individuals were less inclined to establish a culturally responsive classroom environment and facilitate the resolution of interethnic conflicts within the classroom.

Historically both the intention and assumption of the roles that teachers play in classrooms have been focused on teachers’ ability to promote egalitarian attitudes and foster harmony among individuals of different races. Teachers – particularly but not exclusively White teachers – have been found to play a significant role in perpetuating racial inequality that requires attention, intention, and mitigation (Ladson-Billings, 1994; Gershenson et al. 2016). Please see the Mitigation Strategies section of this report for research findings regarding successful interventions.

Systemic Impact

Having explored the intricate ways in which implicit bias can directly impact student outcomes, we now investigate how these biases further manifest in specific areas of the educational system. In the education sector, the role of implicit bias has been linked to racial disparities in school disciplinary actions. Racial disparities play a significant role in both K-12 educational outcomes like high school graduation rates and youth getting caught up in what is now commonly called the “school-to-prison pipeline.” The stakes, therefore, could not be higher for young people.

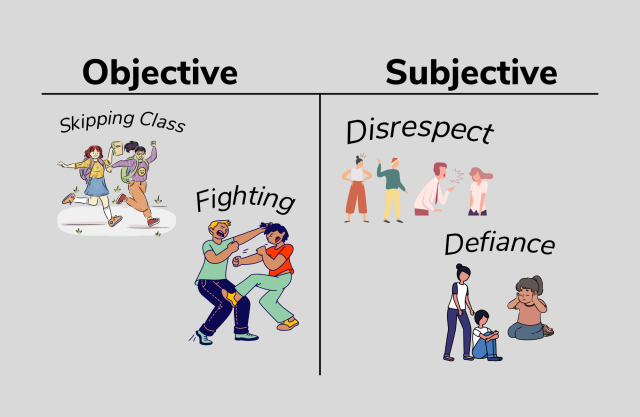

The first area of systemic implicit racial biases’ impact is school discipline. A vast amount of prior research suggests that disciplinary methods in schools affect students of color more than their peers (such as Wallace et al., 2008; Skiba et al., 2011; Hannon et al., 2013). A plethora of studies have found that certain student subgroups face a disproportionate amount of exclusionary discipline (Aud et al., 2011; Nowicki, 2018; U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2015). Implicit racial bias is one of the contributing factors to this problem (Girvan et al., 2017; Goff et al., 2014), particularly under certain conditions, such as when teachers or administrators are making decisions that are ambiguous, demand fast judgement, or when they are physically or mentally drained (Kouchaki & Smith, 2014). Black students were found to be significantly more likely than White students to be labeled as troublemakers, their misbehaviors were more likely to be perceived as indicative of a pattern. Educators also showed a higher tendency to envision themselves suspending a Black student in the future compared to a White student. (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015). The role of implicit bias in school discipline becomes more evident when we examine the disparities for more subjective behavior infractions such as disruption, as opposed to objective infractions like theft (Skiba et al., 2011). Objective infractions are behaviorally defined and based on objective event (e.g., fighting, skipping classes) that often leaves a permanent product, whereas subjective infractions are defined vaguely and more open to subjective interpretation (e.g., defiance, disrespect; Skiba et al., 2002; Theriot & Dupper, 2010). A study of student discipline records from more than 1,800 schools unveiled that these disparities were largely due to racial differences in office discipline referrals for subjectively defined behaviors such as defiance (Girvan et al., 2017). In sum, the past 12 years of studies reveal a troubling trend of systemic unfair treatment of students of color attributable to implicit racial bias.

A second area of systemic implicit racial biases’ impact is the persistent underrepresentation of racially minority students in particular fields, including but not limited to STEM education (McGee, 2021). Two 2018 studies – one in chemical engineering and one in the humanities – explored this impact, as did a cross-disciplinary study of recommendation letters. Farrell and Minerick (2018) examined the stealth nature of implicit bias in the realm of chemical engineering education. They argued that the pervasive presence of implicit bias and stereotype threat creates an environment where educators tend to allocate their time and resources to those students they perceive as more likely to succeed. Such an environment is likely to generate self-fulfilling prophecies and to negatively impact students’ interest in a subject as well as their levels of effort. In the same vein, Holroyd and Saul (2018) provided a detailed discussion of implicit bias in the field of philosophy. The authors suggested that implicit biases might be part of the explanation for the persisting underrepresentation and marginalization of multiple groups in philosophy. For instance, Black PhD students and professional philosophers combined are merely 1.32% of philosophers in the U.S. (Botts et al., 2014). The authors further emphasized the gravity of the situation, noting how implicit biases perpetuate unjust societal structures.

The role of implicit bias is not only limited to direct interactions between educators and students, but it also permeates more indirect aspects of the education system such as recommendation letters. Letters of recommendation, often utilized to evaluate undergraduate students' potential for success as research assistants, interns, or graduate students, can sometimes include implicit bias, thereby potentially impacting decisions and constraining opportunities for underrepresented minorities and students from non-research institutions. Houser and Lemmons (2018) employed a text analysis software to analyze 457 recommendation letters for undergraduates applying for an international research experience, aiming to identify any significant difference in the language used to depict students who were accepted versus those who were rejected. The findings indicate that recommendation letters for successful applicants depict the students' productivity with more certainty and incorporate more student work quotes. Conversely, the letters for unsuccessful applicants contain more positive emotion and mention the students' insight, but also include more discrepancy-associated words (e.g., should) and tentative statements (e.g., perhaps, maybe). The statistically significant results showed the White students tended to be described in relation to their cognitive ability, insightfulness, productivity, and perceptiveness while non-White students tended to be depicted in affective languages and positive emotions.

Taken together, research conducted in 2018 regarding the impact of implicit bias continues to document the deleterious effects of implicit racial bias on students of color as well as an aggregate impact that produces systemic racial disparities. Highlights from 2018 include a theoretical focus on the mechanisms of dehumanization and fear maximization directed at individuals of color. This was complemented by studies that explored the role of implicit bias in teachers’ evaluation, nuances in recommendation letters, and underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority populations across various academic fields. These studies and critical analyses provide a more updated understanding of the scope of implicit racial bias in education, underscoring the urgency for the sector to take meaningful actions.

Implicit Bias in Education: 2019

While there has been an increase in racial and ethnic diversity within the United States, many still live in segregated communities (Logan, 2013). The connection between housing and education segregation further perpetuates inequality from early life through adulthood (Wells et al., 2016). The lack of resources in schools from impoverished and segregated districts exacerbates this vicious cycle of inequality (Rothstein, 2013; Wells et al., 2016). A study by McCardle and Bliss (2019) explored the connection between school segregation and implicit bias, revealing a significant correlation between one’s personal diversity experiences and their levels of implicit bias. Specifically, individuals with more diverse experiences demonstrated lower levels of implicit bias. The complex interplay between implicit bias and education settings served as a focus of burgeoning research, drawing academic attention from 2019 to the manifestation of implicit bias in multiple educational environments, including early childhood, higher education, and special education. In the following section, we will examine publications from 2019 that explore implicit bias in each of these environments.

Early Childhood Education

Shifting our focus to the foundational years, Perszyk and colleagues (2019) aimed to investigate the interplay between racial and gender biases in young children. Considerable evidence indicated that adults tend to evaluate Black men more negatively compared to Black women, White men, and White women (Kang & Bodenhausen, 2015; Navarrete et al., 2010; Purdie‐Vaughns & Eibach, 2008; Sidanius & Veniegas, 2000). This intersectional pattern was also evident in adults' assessments of Black boys (Todd et al., 2016). Specifically, prior research observed that preschool teachers tend to direct their visual attention in a way that suggests they anticipate disruptions from Black boys more than from other racial and gender groups of children (Gilliam et al., 2016). Building upon this foundation, Perszyk et al. focused on preschool-aged children to investigate whether this intersectional bias pattern exists within young children. Utilizing both implicit and explicit measures, the researchers evaluated how 4-year-old children responded to images of children varying in both race (Black and White) and gender (male and female). The results revealed a consistent pro-White bias among children. Furthermore, implicit bias in children was also assessed in racially more homogeneous countries. Qian et al. (2019a) conducted their research to assess the developmental course of implicit bias in Chinese participants. Their study showed that children as young as four years old displayed implicit racial bias towards outgroup members. Setoh et al. (2019) conducted research into the correlation between racial categorization and implicit racial bias in Chinese and Indian preschool children. The study revealed that children's capacity to classify faces by race was connected to their implicit racial bias, rather than their explicit racial bias. This implied that children's subconscious racial bias is linked to their perceptual abilities, rather than their conscious convictions about race. Additionally, the study explicitly considered the assertion that actively teaching children about racial categories might actually increase the prominence of these categories and have unintended consequences.

Special Education

One article in our sample expanded the scope of implicit biases into special education. Building on prior research by Redfield and Kraft (2012), Oelrich (2012), and Fabelo et al. (2011), Dustin Rynders (2019) conducted an in-depth critical exploration of racial disparities in identification, discipline, service, and placement associated with special education. The author’s analyses highlighted evidence that Black students are disproportionately overrepresented in the more subjective disabilities categories such as having emotional disturbance and have a higher chance of being placed in restrictive settings (e.g., a separate, self-contained class; Redfield & Kraft, 2012). Furthermore, it was also found that White teachers refer a disproportionately high number of minority students to special education (Oelrich, 2012). These decisions could adversely affect minority students, given a previous report indicating that nearly 75 percent of special education students have faced suspension or expulsion at least once (Fabelo et al., 2011). Rynders identified implicit bias as one of the contributing reasons for these disparities.

Higher Education

Within the realm of higher education Robinson et al. (2019) compiled narratives delving into the experiences of women of color within a predominantly White academic institution. Through a synthesis of statements from both students and faculty, the article highlighted concerns related to the recruitment, retention, and support of minority faculty and students in higher education. The analysis also exposed the hurdles faced by women of color, such as microaggressions, tokenism, and underrepresentation in leadership roles. Robinson and colleagues argued that implicit bias is one of the key factors contributing to these challenges encountered by women of color. Furthermore, the authors also emphasized the necessity for greater diversity in leadership positions within higher education. Above all, Robinson and colleagues underscored the imperative of equity and inclusivity in society, advocating that acknowledging the absence of equity can catalyze cultural transformation and encourage inclusiveness.

Barbara Applebaum (2019) focuses instead on institutional culture transformation, finding that if taken in isolation implicit bias trainings are not a panacea. She critically assessed the effectiveness of implicit bias training as a means to drive institutional culture transformation within college campuses. The author contended that although implicit bias training is commonly employed as a response to address racism, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of oppression, it is not without its limitations. Applebaum acknowledged the capacity of implicit bias training in effectively raising awareness about unconscious biases. However, she also raised a critique by pointing out training initiatives’ neglect of the structural and systemic factors that perpetuate oppression within the college environment, which may hinder the essential shifts required for transforming the institutional culture in college campuses.

By examining these diverse studies published in 2019, we garner a more nuanced understanding of how implicit bias operates across different educational contexts, ranging from preschools' early racial categorizations to higher education's barriers for women of color and systemic inequalities in special education. The findings and discussions from this section signified an urgent need for multifaceted interventions to disrupt the deeply ingrained biases that perpetuate educational inequities across various age groups and settings. They also underscore the need for attention to the role of implicit bias in the earliest stages of education and resonated with McCardle and Bliss (2019)’s call for investments in our children.

Implicit Bias in Education: 2020

We examined twelve (12) articles published in 2020 that investigated the role of implicit racial bias in educational settings. A number of studies published in 2020 further explored the extent of teachers’ implicit racial bias and its influence on their evaluation of students. Prior literature has documented the links between racial biases held by teachers and racial inequality in education outcomes (Warikoo et al., 2016). 2020 research has revealed that it is possible that even well-intentioned teachers may be unconsciously influenced by their implicit biases, which hinder them from promoting racial equity (Starck et al., 2020).

Starck and colleagues (2020) compared teachers’ implicit bias against those of other adults with similar characteristics using two national datasets. The study found that both teachers and nonteachers have similar levels of pro-White implicit racial bias, indicating that teachers’ racial attitudes largely mirror those held by the broader society. Additionally, Chin and colleagues (2020) found that teachers’ implicit biases across the nation varied by teacher gender and race. Female teachers appeared slightly less biased than non-female teachers, and teachers of color appeared to be less biased than White teachers. Overall, teachers’ adjusted bias levels were lower in counties with higher shares of Black students, echoing the role of contextual factors. When the data were analyzed at an aggregated level, counties with higher levels of implicit racial bias among teachers tended to exhibit more pronounced disparities between Black and White students in both test scores and suspension rates. This finding persists even after adjusting for a broad array of covariates at the county level. Together, these two studies showed that schools and the teachers embedded in them should not be considered as separate entities inherently capable of counteracting societal inequalities independently (Starck, 2020)

Furthermore, Quinn (2020) conducted experimental studies to assess the impact of implicit bias on teachers’ evaluations of student writing. On average, teachers showed a significant implicit association between White students and higher writing competency (Quinn, 2020). Racial bias against Black students was found when teachers scored student writing using vague rubrics. Importantly from a mitigation perspective, racial bias was not found when teachers adhered to rubrics with clearer evaluation criteria. These findings lent support to previous implicit bias research on the relationship of evaluation criteria and teacher’s racial bias (Payne & Vuletich, 2018). Quinn (2020) noted that further research should be conducted to determine the influence of bias on specific academic subjects and the nature of the student work being evaluated.

Controlling for explicit racial bias, Marcucci (2020) conducted a survey with racial priming to examine the potential impact of implicit bias on teachers' disciplinary decision-making. The participating teachers were randomly assigned to either the African American or White condition for the vignette, which served as the racial prime. Subsequently, the teachers were presented with questions regarding their hypothetical responses to the student described in the vignette, specifically addressing disciplinary choices that encompass punitive or rehabilitative approaches. The results indicated that teachers’ implicit bias had a greater impact on punitive disciplinary decisions than on rehabilitative decisions. Counterintuitive to conventional knowledge about anti-Black implicit bias and racial inequalities in discipline, Marcucci (2020) found that teachers treated White students more harshly by making more punitive disciplinary decisions. The author cautioned against interpreting such a finding as evidence for the presence of anti-White implicit bias. Instead, Marcucci (2020) suggested that social desirability might exert a powerful influence on teachers’ decision-making processes in specific contexts. The findings indicated that teachers have the capacity to override anti-Black implicit biases when they are aware of the socially desirable quality for racial neutrality in a reflective setting such as a survey, as opposed to the pressure of a real-time disciplinary interaction. While this overriding tendency may lead to over-correcting standards for White students and lowering expectations for Black students in a harmful manner, it also demonstrated that teachers may be open to engaging in transformative de-biasing strategies. To achieve success in implicit bias mitigation, Marcucci (2020) emphasized the need of restructuring the teaching profession to reduce the cognitive and emotional stress burden on teachers and, consequently, prioritize opportunities for self-reflection.

One recent study investigated the impact of school administrators’ implicit biases on the severity of disciplinary actions (Gullo & Beachum., 2020). With a survey sample of 43 administrators from 22 schools in 7 Pennsylvania school districts, the researchers found that the administrators showed an overall pro-White preference on the Implicit Association Test for race. Discipline data at the individual student-level, including information such as student race, infraction type, disciplinary action, and the deciding administrator for the infraction, was collected from participating districts and schools. It was found that approximately 25% of the differences in discipline severity were based on student race. Most interestingly, the severity of subjective disciplinary decisions, which are not dictated by law, policy, or code, was influenced by administrators’ implicit bias. On the other hand, some of the variations in objective disciplinary decisions were attributed to student race (Gullo & Beachum, 2020). This study is one of the first to demonstrate the influence of administrators’ implicit bias on their subjective discipline decisions.

Taking the findings from Marcucci (2020) and Gullo and Beachum (2020) together, it prompts scholars to consider the multifaceted ways implicit bias manifests itself, showing that it might differ depending on the settings where educational disciplinary practices occur. Marcucci’s controlled, survey setting demonstrated that educators are able to override their implicit biases, leading to unexpected outcomes such as more punitive measures against White students. Marcucci attributed such overriding not to anti-White bias but to the influence of social desirability and a potential over-correction upon reflection. In contrast, Gullo & Beachum's investigation into real-world disciplinary actions confirmed the persistent effect of implicit biases. Their findings showed a pro-White preference among administrators, indicating that a notable proportion of disciplinary disparity can be attributed to implicit racial bias, particularly in subjective decision-making. These findings collectively emphasize the complexity of implicit bias in educational disciplines, particularly how it impacts punitive versus rehabilitative decisions and objective versus subjective decisions. Please see the Mitigation Section for the authors’ recommended solutions.

In summary, the research from 2020 underlined the varying influence of implicit bias across different levels of educators, not just among teachers who interact with students on a daily basis, but also among school administrators who have power to enforce discipline policies or promote applicable changes to them. In our review, we have uncovered divergent ways of how implicit bias influences educators across different contexts. A highlight that stood out is the nuanced impact implicit bias could have on disciplinary practices. It is crucial to recognize that in environments where educators are conscious of scrutiny, the effect of their implicit racial bias could lead to an overcompensation in disciplinary standards for students from different racial backgrounds. On the other hand, in situations where social desirability is not of concern, implicit bias continues to be associated with disparate subjective disciplinary decisions, leading to unjust treatment of certain student populations. While teachers and administrators may have every good intention to support all students equally, their behaviors and judgments are influenced by both their own implicit bias and deeply embedded systemic biases. These findings come at a crucial time, especially considering the anticipated demographic shift in U.S. schools where the number of racial and ethnic minority students are expected to surpass that of their non-minority peers (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2017).

Mitigating Bias in Education

Studies from 2018-2020 did not simply continue to confirm the last ten or more years of evidence, supporting a direct link between implicit racial bias and educational policies and outcomes. Many studies also proposed and/or tested mitigation strategies, which has led to a crucial debate: Should the focus be on fixing the implicit bias held by students and teachers through awareness training, or should efforts be concentrated at the policy level? Girvan and colleagues (2017) found evidence for the former, showing that when explicit guidelines are provided, individuals are more likely to make equitable decisions. However, just making each individual accountable for their biased decisions isn't enough. Anyon and colleagues (2018) argued for the necessity of examining specific school settings as a more systemic factor that creates discrepancies in discipline. Their study showed that it is the classroom environment itself that contributes most substantially to the disciplinary disparity among students of color. Furthermore, Tate and Page (2018) raised critiques about individual level implicit bias training. They argued that we must recognize that biases are often interlinked with broader institutional and systemic structures, emphasizing the unconscious nature of implicit bias may downplay the role of White supremacy in maintaining racism. Arlo Kempf (2020) also pointed out that the implicit bias perspective may provide a corporate-friendly lens for understanding racism at the individual level, but it is not enough for disrupting racism at the institutional and structural levels. He called for the use of critical race theory and critical pedagogy as tools to deepen implicit bias intervention approaches.

Heidi Vuletich and Keith Payne (2019) highlights the importance of considering the impact of systemic factors, such as campus-specific social indicators and faculty diversity, on the stability of individual implicit biases. They delved into the critical question of whether implicit bias can be mitigated in the long-term, and if so, under what conditions. Bearing these questions in mind, they revisited a prior study which indicated that although interventions altered participants' bias immediately after, the effects were not sustained over time (Lai et al., 2016, Study 2). To investigate whether the stability observed in implicit bias reflected persistent individual attitudes or stable environments on campus, Vuletich and Payne reanalyzed the data collected across 18 university sites by Lai and colleagues and identified three measures capturing historical and present inequalities that could potentially influence university community members today. The three measures are: 1) public display of structural inequality (evaluating whether Confederate monuments were displayed on campuses), 2) faculty diversity (a measure reflecting underrepresentation of minority faculty as a signal of institutional inequalities), and 3) campus-specific social mobility (derived from a study estimating social mobility in U.S. universities). Lai and colleagues had previously interpreted the short-lived effects of their interventions as showing that individual’s implicit biases are difficult to change. However, Vuletich and Payne’s further analyses found that the stability of individual implicit biases should be attributed to campus environments reflecting historical and present inequalities. This reinterpretation has important implications for combating discrimination as it suggests that altering the social environment may be more effective than attempting to change individual attitudes. The findings also suggested that eliminating environmental cues of inequality, like Confederate monuments, could potentially reduce overall implicit bias. Similarly, enhancing faculty diversity at universities or diversifying leadership roles within organizations may lead to sustained institutional bias changes.

As we did in the introduction, we classified mitigation strategies into three categories: students, educators, and systems. Table 1 below presents a summary of the mitigation strategies derived from our review of the implicit bias intervention literature, specifically focusing on education published between 2018 and 2020. Each strategy is hyperlinked to facilitate easier navigation for reader.

Mitigation Strategies for Students’ Implicit Biases | |

Davis (2020); | |

Behm-Morawitz &Villamil (2019); | |

Mitigating Implicit Bias Among Educators | |

Provide Voluntary Professional Development Workshops to Educators | Aguilar (2019); |

Holroyd & Saul, 2018; | |

Systemic and Policy-Oriented Mitigation Strategies | |

Gullo & Beachum’s (2020); | |

Clark-Louque & Sullivan (2020); | |

Applebaum (2019); | |

Mitigation Strategies for Students’ Implicit Biases

1. Leverage the Critical Window of Early Childhood Education

Several studies suggest that early education presents a crucial window for addressing implicit bias, including five studies from our samples: two studies by Qian et al., 2019a and 2019b; Setoh et al., 2019; McCardle and Bliss, 2019; and Davis, 2020. The first study by Qian et al. (2019a) found that implicit racial bias against outgroup members was evident in Chinese participants as young as four years old and that implicit anti-Black bias remained stable across the age range from 4 to 19 years old. This finding underscored that implicit racial bias develops at a young age. Returning to Setoh and colleagues’ 2019 study, which recommended that future research should delve into the role of social experiences in shaping children's understanding of racial categories, the authors proposed a perceptual training approach aimed at reducing children’s automatic inclination to categorize faces based on race, potentially fostering better interracial reactions. Qian et al.’s second study (2019b) did exactly that by shedding light on the development of face-related social processing. This study also offers practical strategies for mitigating implicit racial bias in young children.

Qian and colleagues (2019b) assessed the long-term impact of perceptual individuation training on reducing implicit racial bias in preschool children. The study tracked 95 Chinese preschool children across a period of 70 days. Two perceptual individuation trainings, one initial and one supplementary, were carried out to teach preschoolers to focus on distinctive facial features rather than relying on stereotypes or group attributes. Implicit racial bias was measured at five time points, including before and immediately after each training, as well as 9, 10, and 70 days after the pretest. Results revealed that perceptual individuation training effectively reduced implicit racial bias in preschool children. Specifically, this bias reduction was observed both immediately after the initial training and 70 days after the pretest. These practical approaches could be integrated into school curriculum or utilized by social workers, as suggested by McCardle and Bliss (2019), to address individual factors leading to segregation in the society.

Furthermore, in the wake of the tragic events involving George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, Thamara Davis (2020) discussed the importance of addressing diversity, fair treatment, implicit bias, and racial trauma, particularly in the context of educating young children. She argued that such news events can emotionally impact children, potentially leading to chronic stress, similar to their effects on adults. On the other hand, these events also offer opportunities to teach about privilege, racism and implicit bias. The articles we reviewed documented that children as young as four years old have exhibited implicit racial bias against outgroup members. Therefore, avoiding these topics during this critical window may have unintended consequences. Avoiding discussions on these topics, even with young children, might foster the misconception that race is a taboo topic or create a space where prejudice and bias develop. Davis contended that parents, educators and healthcare professionals should all play a role in holding discussions about implicit bias, as well as the trauma and anxiety surrounding racial violence.

2. Embrace Multicultural Education

A second mitigation strategy we identified in our review of all 33 publications between 2018 to 2020 is an embrace of multicultural education. Multiculturalism can be described as a social and intellectual movement that upholds diversity as a fundamental principle and advocates for the equitable treatment and respect of all cultural groups (APA, 2017). This approach encompasses the incorporation of educational materials and activities designed to foster multicultural awareness, such as diversity quizzes and videos on cultural sensitivity. Three studies from our sample concurred with this strategy.

Behm-Morawitz and Villamil (2019) turned our attention to the digital realm and investigated the effectiveness of innovative online diversity training in higher education. Specifically, the research examines how an online program impacts undergraduate students' attitudes toward diversity, motivation to control prejudice, and bias reduction toward African Americans. The study discussed a comprehensive approach to assessing bias, employing both direct (self-report) and indirect measures. With the indirect measure of the Implicit Association Test (IAT) to gauge implicit bias against African Americans, the results revealed that completing the online diversity program led to decreased implicit bias and enhanced openness to diversity. Furthermore, the researchers found that lessons addressing identity, stereotyping, housing discrimination, and education discrimination are particularly effective in engaging students with intergroup-based diversity instruction. Additionally, Behm-Morawitz and Villamil noted that the classroom setting is susceptible to society’s evolving and diverse worldviews. Therefore, when drafting online diversity training programs, it is crucial to consider the polarized U.S. political climate and students' diverse perspectives, employing strategies such as interactive language and a second person viewpoint to draw viewers into a deeper engagement with the materials being presented. McCardle and Bliss (2019) expanded on this conversation by suggesting school integration can be seen as a strategy to promote multiculturalism as well. Their study observed a direct correlation between perceived diverse experiences and reduced implicit bias. This finding indicated that school integration could provide students with more diverse life experiences, which would better equip students’ adult life in a multiracial society by allowing more opportunities to have genuine interactions with people from different racial, regional, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Black and Li (2020) based their research on previous culture-related studies and hypothesized that cultivating multiculturalism can be a possible solution to mitigating intergroup bias problems. For instance, trainings that emphasized cultural awareness and diversity issues were found to be a useful tool for the on-the-job education of healthcare professionals to improve cultural competency (Smith, 1998), self-awareness of cultural bias (Carter et al., 2006), and reduce stigmatization (Hayes et al., 2004). Such training programs were shown to be effective on both educators and students of different ages in improving attitude to and social engagement with outgroup members of different races and ethnicities (Turner & Brown, 2008; Warring et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 2010). In the context of this study, intervention techniques were employed to familiarize participants with educational materials centered around multiculturalism. Black and Li’s 2020 experimental study involved random assignment of 249 undergraduate students to intervention or control conditions and found that their virtual intervention strategies successfully increased multiculturalism scores among undergraduate students. Five major sets of activities were contained in the educational materials, including a diversity awareness quiz, “My Multicultural self”; cultural sensitivity scenarios; microaggression-related educational videos, cultural appropriation, and implicit bias; and scenarios illustrating advocacy and taking proactive measures against racism. The authors argued that multiculturalism may positively influence implicit and explicit cultural attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors. This positive result of intervention demonstrates the possibility of using inexpensive and time-efficient methods to address biases in student populations.

Mitigating Implicit Bias Among Educators

1. Voluntary Professional Development Workshops:

One of the more traditional ways of mitigating implicit bias at individual level is through workshops and training programs for teachers to raise awareness about implicit bias and offer tools for introspection and self-improvement. Equipping educators with the tools they need to combat implicit bias and foster equitable educational environments is a crucial tool for disrupting the harms students of color often face due to implicit racial bias in the classroom. Our review identified four (4) studies over the three-year period that focused specifically on professional development training for educators.

Educators may not consciously endorse stereotypes, but implicit racial bias is sufficient to make an individual quickly perceive youth of color, particularly males, as threatening and justify punitive measures against them (Brown, 2018; Eberhardt et al., 2004; Mendez et al., 2002; Skiba et al., 2011; Wallace et al., 2008). Therefore, it is crucial for educators to disrupt the perpetuation of dysfunctional educational ecologies by learning and understanding the racial discourses that inform implicit bias in schools (Annamma & Morrison, 2018). Aguilar (2019) explored the potential impact of mindfulness and awareness cultivation on educators' ability to recognize and disrupt unconscious biases, leading to a reduction in opportunity gaps within educational institutions. Aguilar (2019) emphasized the importance of acknowledging the concept of race as a detrimental narrative that perpetuates inequities in education, including the belief that students from specific backgrounds possess diminished capabilities or that certain student groups are predisposed to behavioral issues. These narratives can foster implicit biases that impact educators' interactions and support for students, thus contributing to the persistence of opportunity gaps. To address this issue, Aguilar (2019) provided an illustrative example of a mindfulness professional development session implemented in school, as a result of this session, educators were able to proactively intercept racist thoughts as they arise, enabling them to consciously choose their responses and actions.

In their study of women of color students and faculty, Robinson et al. (2019) proposed remedies such as creating new courses centered on diversity and inclusivity, establishing safe spaces for discussions on race and sensitive topics, involving faculty in sensitivity training, and forming affinity groups to address the needs of students of color. Additionally, drawing from a previous study (Jackson et al., 2014), Robinson et al. reiterated the effectiveness of diversity training in reducing stereotypes in STEM fields and fostering a more inclusive environment. Robinson and colleagues concluded that educational institutions should prioritize support programs involving mentoring to effectively recruit and retain diverse students and faculty.

Harrison-Bernard and colleagues (2020) documented the processes and results of a professional development workshop on implicit bias held at a university. The six workshops consisted of various didactic teaching modules, active participation, and discussions aimed at increasing participants’ introspection and implicit bias awareness. Pre- and post-workshop surveys were conducted to assess participants’ self-perception of knowledge and behaviors related to diversity and implicit bias. The surveys showed that participants’ knowledge of implicit bias increased significantly as a result of the workshops. Moreover, an observational study of a single 90-minute racial affinity caucusing workshop was also conducted to for educators interested in racial health disparities (Guh et al., 2020). The workshop successfully improved participants’ impression of and confidence in implementing racial affinity caucusing. Both studies effectively demonstrate that educators’ knowledge and attitudes regarding implicit bias intervention tools can be changed even in a much shorter period of time. These studies called attention to the need for effective tools to teach and remedy the impact of implicit racial bias in education.

2. Foster Empathy and Equal Expectations for All Students

Empathy-based intervention has been using in various areas of study, such as teacher-student interaction (Okonofua et al., 2016) and healthcare-related education (Batt-Rawden et al., 2013; McGuire, 2016). Research findings exemplified by the Whitford and Emerson (2019) study showcased the potential of empathy interventions to mitigate implicit bias among pre-service teachers. The authors conducted an experiment to examine whether a brief empathy-inducing intervention could reduce implicit bias among pre-service teachers who planned to work in elementary schools. This intervention required participants to read 10 instances of racism that Black students encountered. Subsequently, participants were asked to put themselves in the students' situations, express their feelings about the experiences, detail how they would react in those scenarios, describe the potential emotions of growing up in such an environment, and suggest ways to prevent similar experiences in the future. The results showed that the empathy intervention significantly decreased implicit bias among White female pre-service teachers towards Black individuals. School discipline disparities contribute to the prison pipeline for at-risk students (Skiba et al., 2014). Empathy intervention conducted in Whitford and Emerson could serve as a foundation for promoting change and addressing implicit bias in education.

In addition to the cultivation of empathy, another similar theme also surfaced from our synthesis, underscoring the imperative of fostering equal consideration for students from diverse backgrounds. Researchers have urged educators to maintain high expectations for all students, while also being vigilant about the harmful effects of stereotype threats. This is particularly crucial for fields such as STEM education and philosophy, where minority students are severely underrepresented (Haring-Smith, 2012; Holroyd & Saul, 2018; Farrell & Minerick, 2018). In their 2018 study on chemical engineering education, Farrell and Minerick drew our attention to the fact that, due to implicit biases, educators often direct their time and resources toward students they deem most likely to be successful. To combat these challenges, the authors suggested that both students and educators have responsibilities in addressing them. Students should strive to be more mature and adaptive problem-solvers, while of course fulfilling class requirements to the best of their abilities., Educators should employ as objective a grading system as possible. Furthermore, educators should acknowledge their implicit biases, pursue self-education regarding these biases, and remain cognizant of stereotype threat and its negative impacts on students. Educators also need to send consistent messages of high expectations and anticipated success to all students in the class. Importantly, educators should not perceive limited prior experience and low confidence in engineering as deficits as these are common traits for students from underrepresented groups in engineering. Instead, these characteristics should be considered as indicators of assets that may aid students in their journey to becoming engineers.

Systemic and Policy-Oriented Mitigation Strategies

1. Utilize Objective Decision-Making Standards

The objective decision-making standards approach involves the application of data-driven methodologies and explicit guidelines to identify, analyze, and address disciplinary disparities. McIntosh and colleagues (2018) deepened scholars’ engagement with the approach by testing a four-step, data-driven decision-making strategy. This method helps to identify the interactions that are susceptible to implicit bias and then tailors the environment to meet all students' needs. The first step, problem identification, involves calculating disproportionality metrics by incorporating both risk ratios and absolute rates by subgroups. The metrics will establish the baseline for monitoring progress. Next, during the problem analysis step, potential causes for the disproportionality are identified. Tools such as the School-Wide Information System (SWIS) are recommended for examination of discipline patterns such as location, time of day, and type of behavior by subgroup. The third step is plan implementation, in which existing systems are evaluated and potentially revised to better meet student needs. McIntosh et al. (2018) recommended a flexible, proactive, multi-tiered behavioral approach that incorporates explicit expectations and accommodates the needs of students, families, and the community. This approach also promotes objective discipline procedures, such as clearly defining problematic behaviors. Finally, in the plan evaluation step, the implementation of the plan is assessed through established measures, and the original disproportionality metrics are recalculated. These are then compared with the initially identified equity goals. In a case study using this approach, McIntosh et al. (2018) noted a consistent decrease in discipline disproportionality, reinforcing the effectiveness of this objective, data-driven strategy. Gullo and Beachum's 2020 study also highlighted the importance of having clear and objective policy guidelines and procedures to help reduce the racial discipline. They also emphasized the need for schools to make efforts to expand objective policies and remove the subjective nature of many disciplinary decisions when possible.

2. Replace Negative Impact Policies with Restorative Measures

Much of the research at the systemic level has focused on the alarming disparities in K-12 school discipline. School discipline disparities contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline for marginalized students (Skiba et al., 2014). Existing policies in the current education system sometimes inadvertently contribute to the disproportionately high rates of disciplinary actions against marginalized student populations. Zero Tolerance policies are one of them (Clark-Louque & Sullivan, 2020). Zero Tolerance was originally developed and introduced to public schools in an effort to make schools safer. It operates under two basic assumptions: 1) harsh disciplines will deter student misconduct, and 2) removal of students who committed the most serious offenses will benefit the school. However, these assumptions are problematic as school principals’ attitudes are subjective and can be influenced by implicit racial bias. Recently, Zero Tolerance policies have expanded to include relatively minor issues such as dress code violations, disrespect, and willful defiance, which were observed among the common infractions leading to suspension. Notably, disrespect and willful defiance are subjective concepts which, when applied, are rife with the risk of implicit racial bias influence due to their vagueness – everyone has their own understanding of respect and defiance (Girvan et al., 2017; Skiba et al., 2002; 2011). Excessive reliance on punitive forms of discipline such as suspension was directly linked to students’ tendencies to drop out of school susceptibility to being ensnared by the criminal justice system (Fergus, 2015).

At the school administration level, Clark-Louque and Sullivan (2020) discussed the disproportionate discipline consequences faced by Black girls and linked it to the implicit biases held by some school officials. They argued that these biases, which are based on stereotypes that see Black women and girls as hypersexual, sassy, conniving, or loud (Morris, 2016), distort the views of school officials towards Black girls and resulted in the disciplinary actions taken based on Zero Tolerance policies. Clark-Louque and Sullivan (2020) presented two real-life scenarios in which Black female students were suspected of using marijuana. In one scenario, the school administration followed a Zero Tolerance approach, while in the second scenario the administration adopted a restorative and equity-based partnering approach such as asking questions that allow students to express themselves and inviting students to sign up for counseling. Under the first scenario, the student involved was eventually expelled. The four students involved in the second scenario, however, were given an opportunity to meet with the school counselor and their families were notified regarding safety concerns and future possible engagement strategies. Based on their findings the researchers strongly recommended that school administrators should guard against implicit and explicit biases by adopting restorative practices and build culturally proficient partnerships with student families instead of relying heavily on Zero Tolerance practices.

Furthermore, Romero and colleagues (2020) reviewed a number of promising studies that may shed light on how to alleviate implicit bias in school discipline. Their review showed that less punitive alternatives such as restorative justice, as opposed to the Zero Tolerance approach, are gaining popularity in schools. Romero and colleagues recommended training and intervention strategies to educators, including empathetic mindset training, motivated self-regulation, and prejudice habit-breaking interventions. The researchers emphasized that mitigating implicit bias in schools requires a sustained approach that raises awareness of implicit bias and its consequences in educational settings. This calls for the inclusion of individual level implicit bias assessments coupled with careful feedback on the results and sustained professional development.

Marcucci (2020) also championed restorative measures. Her study found that implicit bias appeared to have less influence on rehabilitative disciplinary decisions compared to punitive ones. According to Marcucci (2020), restorative practices are able to compel students and educators to find novel ways of interaction, which may humanize the students and allow educators to reflect and disrupt automatic and unconscious biased thinking. Echoing Marcucci (2020)’s findings, McIntosh and colleagues further underscored this perspective with their flexible four-step behavioral approach that exemplified the restorative measures. By pinpointing “physical aggression on the playground” as a specific vulnerable decision point that increases the likelihood of implicit bias affecting discipline decision making, the research team advised educators to set clear expectations and meet the needs of students, families, and the community. This restorative approach fosters objective discipline procedures, which have resulted in a consistent decrease in disciplinary disparity over time.

3. Utilize a Holistic Approach

The first two systemic mitigation strategies lead us to a third and final strategy: using a holistic approach. By this we mean crafting approaches that include but are not limited to mitigating implicit racial bias. This approach complements individual-level interventions by addressing the broader environmental factors that contribute to implicit bias, suggesting that sustained change may require a comprehensive strategy that includes altering the social environment.

Applebaum’s critical read of implicit bias trainings is one example. In lieu of an exclusive reliance on implicit bias training, Applebaum advocated for a more comprehensive and holistic approach that attends to systemic as well as individual and intergroup factors. Another example is proposed by Rynders (2019), who provided possible legal solutions that lawyers can employ in the courtroom and within their own practice to address implicit bias. These solutions include using expert witnesses to testify about implicit bias, using data to show disproportionality, and advocating for culturally responsive teaching practices. At the end of his discussion, Rynders called for educators and advocates to acknowledge the impact of implicit bias in these disparities and integrate research-based approaches to mitigate racial biases. He also emphasized the role of attorneys in education, asserting that special education lawyers should address racial and national origin discrimination as necessary and partner with racial justice organizations to attain educational equity.

In a similar vein, Holroyd and Saul (2018) widened the discussion to include faculty hiring and professional development. They emphasized the need for proactive strategies to counter these biases in decision-making and interactions. To specifically address the entrenched issue of implicit bias in philosophy, they offered various reform suggestions, including: diversifying the subject matter taught, setting hiring criteria in advance, and reducing dependence on letters of recommendation as a key element in faculty selection.

In response to racially disproportionate expulsion rates in preschools (Meek & Gilliam, 2016), Davis and colleagues (2020) take a more systemic approach to combating implicit bias in early education. Their theoretical framework, the Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation (IECMHC), can reduce the influence of implicit bias on educators’/teachers’ disciplinary decisions. IECMHC was developed to account for the roles played by mental health consultants in building teachers’ capacities to support the healthy social-emotional development of young children. The framework underlined the power of a strong consultative alliance between teachers and consultants with expertise in infant and early childhood mental health. This consultative alliance can be built through multiple core tasks, including: asking reflective questions, creating a holding environment for others’ emotions, raising issues of race and gender, cultivating cultural awareness, and exploring contextual influences such as parenting, trauma, cultural expectations, and developmental differences. A strong consultative alliance, in turn, can contribute to increases in reflective capacity and changes in teachers’ perspective and behavior, both of which are expected to reduce the influence of implicit bias on expulsion rates. In addition to professional help, facilitated workshops for teachers and staff members have also been created and implemented.

Building on the aforementioned strategies, the final mitigation strategy we have identified focuses on transforming the campus environment as a whole. As we noted earlier, Vuletich and Payne's (2019) findings offered us a roadmap for this transformative approach. Their findings emphasized the power of environmental cues on campus, such as Confederate monuments and level of faculty diversity, in perpetuating biases. By addressing these historical and present inequalities embedded within the campus environment, universities have the potential to significantly reduce implicit bias.

References

Aguilar, E. (2019). Getting mindful about race in schools. Educational Leadership, 76(7), 62-67.

American Psychological Association. (2017). Multicultural guidelines: An ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. http://www.apa.org/about/policy/multicultural-guidelines.aspx

Annamma, S., & Morrison, D. (2018). Identifying dysfunctional education ecologies: A DisCrit analysis of bias in the classroom. Equity & Excellence in Education, 51(2), 114-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2018.1496047

Anyon, Y., Lechuga, C., Ortega, D., Downing, B., Greer, E., & Simmons, J. (2018). An exploration of the relationships between student racial background and the school sub-contexts of office discipline referrals: A critical race theory analysis. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(3), 390-406. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2017.1328594

Applebaum, B. (2019). Remediating campus climate: Implicit bias training is not enough. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 38, 129-141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9644-1

Aud, S., KewalRamani, A., & Frohlich, L. (2011). America's youth: Transitions to adulthood (NCES 2012-026). National Center for Education Statistics. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED527636.pdf

Banks J. A., Cochran-Smith M., Moll L., Richert A., Zeichner K., LePage P., Darling-Hammond L., Duffy H., McDonald M. (2005). Teaching diverse learners. In Darling-Hammond L., Bransford J. (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 232–274). Jossey-Bass.

Batt-Rawden, S. A., Chisolm, M. S., Anton, B., & Flickinger, T. E. (2013). Teaching empathy to medical students: An updated, systematic review. Academic Medicine, 88(8), 1171–1177. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299f3e3

Behm-Morawitz, E., & Villamil, A. M. (2019). The roles of ingroup identification and implicit bias in assessing the effectiveness of an online diversity education program. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 47(5), 505-526. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2019.1678761

Black, K., & Li, M. (2020). Developing a virtual multicultural intervention for university students. Behavioral Sciences, 10(11), 186-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2020.1832014

Botts, T. F., Bright, L. K., Cherry, M., Mallarangeng, G., & Spencer, Q. (2014). What is the state of blacks in philosophy?. Critical Philosophy of Race, 2(2), 224-242. https://doi.org/10.5325/critphilrace.2.2.0224

Brown, A. (2018). From subhuman to human kind: Implicit bias, racial memory, and black males in schools and society. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(1), 52-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2017.1403176

Carter, M. M., Lewis, E. L., Sbrocco, T., Tanenbaum, R., Oswald, J. C., Sykora, W., Williams, P., & Hill, L. D. (2006). Cultural competency training for third-year clerkship students: Effects of an interactive workshop on student attitudes. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(11), 1772–1778.

Chin, M. J., Quinn, D. M., Dhaliwal, T. K., & Lovison, V. S. (2020). Bias in the air: A nationwide exploration of teachers’ implicit racial attitudes, aggregate bias, and student outcomes. Educational Researcher, 49(8), 566–578.https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20937240

Clark-Louque, A., & Sullivan, T. A. (2020). Black girls and school discipline: Shifting from the narrow zone of zero tolerance to a wide region of restorative practices and culturally proficient partnerships. Journal of Leadership, Equity, and Research, 6, Article 2.

Correll, J., Park, B., Judd, C. M., & Wittenbrink, B. (2002). The police officer's dilemma: Using ethnicity to disambiguate potentially threatening individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1314–1329.

Davis, A. E., Perry, D. F., & Rabinovitz, L. (2020). Expulsion prevention: Framework for the role of infant and early childhood mental health consultation in addressing implicit biases. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(3), 327-339. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21847

Davis, L. (2013). Introduction: Disability, normality and power. In Lennard J Davis (Ed.), The disability studies reader (pp. 1-14). Taylor & Francis.

Davis, T. (2020). The role of parents, educators, and treatment providers in educating children about racial injustice. The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter, 36(9), 8-8.

Eberhardt, J. L., Goff, P. A., Purdie, V. J., & Davies, P. G. (2004). Seeing Black: Race, crime, and visual processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 876–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.876

Fabelo, T., Thompson, M. D., Plotkin, M., Carmichael, D., Marchbanks, M. P., III, & Booth, E. A. (2011). Breaking school's rules: A statewide study of how school discipline relates to students' success and juvenile justice involvement. Council of State Governments Justice Center; Public Policy Research Institute of Texas A&M University. https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Breaking_Schools_Rules_Report_Final.pdf

Farrell, S., & Minerick, A. (2018). Perspective: The stealth of implicit bias in chemical engineering education, its threat to diversity, and what professors can do to promote an inclusive future. Chemical Engineering Education, 52(2), 129-135.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (2017). Race and Hispanic origin composition: Percentage of U.S. children ages 0–17 by race and Hispanic origin, 1980–2017 and projected 2018–2050. Forum on Child and Family Statistics. https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables/pop3.asp

Fergus, E. (2015). A breakthrough on discipline. National Association of Elementary School Principals. https://www.naesp.org/principal-novemberdecember-2015-breaking-cycle/breakthrough-discipline

Forgiarini, M., Gallucci, M., & Maravita, A. (2011). Racism and the empathy for pain on our skin. Frontiers in psychology, 2, Article 108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00108

Gershenson, S., Holt, S. B., & Papageorge, N. W. (2016). Who believes in me? The effect of student–teacher demographic match on teacher expectations. Economics of Education Review, 52, 209-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.002

Gilliam, W. S., Maupin, A. N., & Reyes, C. R. (2016). Early childhood mental health consultation: Results of a statewide random-controlled evaluation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(9), 754–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.006

Girvan, E. J., Gion, C., McIntosh, K., & Smolkowski, K. (2017). The relative contribution of subjective office referrals to racial disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Quarterly: The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 32(3), 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000178

Goff, P. A., Eberhardt, J. L., Williams, M. J., & Jackson, M. C. (2008). Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292

Goff, P. A., Jackson, M. C., Di Leone, B. A. L., Culotta, C. M., & DiTomasso, N. A. (2014). The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 526–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035663

Guh, J., Krinsky, L., White-Davis, T., Sethi, T., Hayon, R., & Edgoose, J. (2020). Teaching racial affinity caucusing as a tool to learn about racial health inequity through an experiential workshop. Family Medicine, 52(9), 656-660. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2020.596649

Gullo, G. L., & Beachum, F. D. (2020). Does implicit bias matter at the administrative level? A study of principal implicit bias and the racial discipline severity gap. Teachers College Record, 122(3), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812012200309

Hannon, L., DeFina, R., & Bruch, S. (2013). The relationship between skin tone and school suspension for African Americans. Race and Social Problems, 5(4), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-013-9104-z

Haring-Smith, T. (2012). Broadening our definition of diversity. Liberal Education, 98(2), 6-13.

Harrison-Bernard, L. M., Augustus-Wallace, A. C., Souza-Smith, F. M., Tsien, F., Casey, G. P., & Gunaldo, T. P. (2020). Knowledge gains in a professional development workshop on diversity, equity, inclusion, and implicit bias in academia. Advances in Physiology Education, 44(3), 286-294. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00164.2019

Hayes, S. C., Bissett, R., Roget, N., Padilla, M., Kohlenberg, B. S., Fisher, G., ... & Niccolls, R. (2004). The impact of acceptance and commitment training and multicultural training on the stigmatizing attitudes and professional burnout of substance abuse counselors. Behavior therapy, 35(4), 821-835. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80022-4

Holroyd, J., & Saul, J. (2018). Implicit bias and reform efforts in philosophy. Philosophical Topics, 46(2), 71-102.

Houser, C., & Lemmons, K. (2018). Implicit bias in letters of recommendation for an undergraduate research internship. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(5), 585-595. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1301410

Jackson, S. M., Hillard, A. L., & Schneider, T. R. (2014). Using implicit bias training to improve attitudes toward women in STEM. Social Psychology of Education, 17, 419-438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9259-5

Jacoby-Senghor, D. S., Sinclair, S., & Smith, C. T. (2015). When bias binds: Effect of implicit outgroup bias on ingroup affiliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(3), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039513

Kang, S. K., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2015). Multiple identities in social perception and interaction: Challenges and opportunities. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 547–574. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015025

Kempf, A. (2020). If we are going to talk about implicit race bias, we need to talk about structural racism: Moving beyond ubiquity and inevitability in teaching and learning about race. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, Special Issue: 50 Years of Critical Pedagogy and We Still Aren’t Critical, 19(2), Article 10.

Kouchaki, M., & Smith, I. H. (2014). The morning morality effect: The influence of time of day on unethical behavior. Psychological Science, 25(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613498099

Kumar, R., Karabenick, S. A., & Burgoon, J. N. (2015). Teachers’ implicit attitudes, explicit beliefs, and the mediating role of respect and cultural responsibility on mastery and performance-focused instructional practices. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(2), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037471

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). What we can learn from multicultural education research. Educational leadership, 51(8), 22-26.

Lai, C. K., Skinner, A. L., Cooley, E., Murrar, S., Brauer, M., Devos, T., Calanchini, J., Xiao, Y. J., Pedram, C., Marshburn, C. K., Simon, S., Blanchar, J. C., Joy-Gaba, J. A., Conway, J., Redford, L., Klein, R. A., Roussos, G., Schellhaas, F. M. H., Burns, M., . . . Nosek, B. A. (2016). Reducing implicit racial preferences: II. Intervention effectiveness across time. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(8), 1001–1016. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000179

Logan J. R. (2013). The Persistence of segregation in the 21st century metropolis. City & Community, 12(2), 160-168. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12021

Marcucci, O. (2020). Implicit bias in the era of social desirability: Understanding antiblackness in rehabilitative and punitive school discipline. The Urban Review, 52(1), 47-74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-019-00512-7

McCardle, M., & Bliss, S. (2019). Digging deeper: The relationship between school segregation and unconscious racism. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 89(2), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377317.2019.1686929

McGee, E. O. (2021). Black, brown, bruised: How racialized STEM education stifles innovation. Harvard Education Press.

McGuire, J. M., Bynum, L. A., & Wright, E. (2016). The effect of an elective psychiatry course on pharmacy student empathy. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 8, 565–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2016.03.005

McIntosh, K., Ellwood, K., McCall, L., & Girvan, E. J. (2018). Using discipline data to enhance equity in school discipline. Intervention in school and clinic, 53(3), 146-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451217702130

Meek, S.E., & Gilliam, W.S. (2016). Expulsion and suspension in early education as matters of social justice and health equity. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC.

Mendez, L. M. R., Knoff, H. M., & Ferron, J. M. (2002). School demographic variables and out-of-school suspension rates: A quantitative and qualitative analysis of a large, ethnically diverse school district. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10020

Morris, M. W. (2016). Pushout: The criminalization of Black girls in school. The New Press.

Navarrete, C. D., McDonald, M. M., Molina, L. E., & Sidanius, J. (2010). Prejudice at the nexus of race and gender: An outgroup male target hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(6), 933–945. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017931

Nosek B. A., Smyth F. L., Hansen J. J., Devos T., Lindner N. M., Ranganath K. A., Smith C. T., Olson K. R., Chugh D., Greenwald A. G., Banaji M. R. (2007). Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. European Review of Social Psychology, 18, 36–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280701489053

Nowicki, J. M. (2018). K-12 Education: Discipline disparities for Black students, boys, and students with disabilities (GAO-18-258). U.S. Government Accountability Office. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED590845.pdf

Oelrich, N. M. (2012). New idea: Ending racial disparity in the identification of students with emotional disturbance. South Dakota Law Review, 57(1), 9-41.

Okonofua, J. A., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2015). Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological Science, 26(5), 617–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615570365

Okonofua, J. A., Paunesku, D., & Walton, G. M. (2016). Brief intervention to encourage empathic discipline cuts suspension rates in half among adolescents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(19), 5221–5226. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523698113

Parekh, G., Brown, R. S., & Zheng, S. (2018). Learning skills, system equity, and implicit bias within Ontario, Canada. Educational Policy, 35(3), 395–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904818813303

Payne, B. K., & Vuletich, H. A. (2018). Policy insights from advances in implicit bias research. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(1), 49-56. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732217746190

Perszyk, D. R., Lei, R. F., Bodenhausen, G. V., Richeson, J. A., & Waxman, S. R. (2019). Bias at the intersection of race and gender: Evidence from preschool‐aged children. Developmental Science, 22(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12788

Purdie-Vaughns, V., & Eibach, R. P. (2008). Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 59(5-6), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9424-4

Qian, M. K., Heyman, G. D., Quinn, P. C., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2019a). Differential developmental courses of implicit and explicit biases for different other-race classes. Developmental Psychology, 55(7), 1440-1452. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dev0000730

Qian, M. K., Quinn, P. C., Heyman, G. D., Pascalis, O., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2019b). A long‐term effect of perceptual individuation training on reducing implicit racial bias in preschool children. Child Development, 90(3), e290-e305. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12971

Quinn, D. M. (2020). Experimental evidence on teachers’ racial bias in student evaluation: The Role of grading scales. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(3), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373720932188