State of the Science: Implicit Bias 2018-2020

State of the Science: Implicit Bias 2018-2020Xiaodan Hu, PhD & Ange-Marie Hancock, PhD | Published 02:30 p.m. ET May 22, 2024.

Cite this article (APA-7): Hu, X., & Hancock, A. M. (2024). State of the science: Introduction to implicit bias review 2018-2020. The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. https://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/state-science-introduction-implicit-bias-review-2018-2020

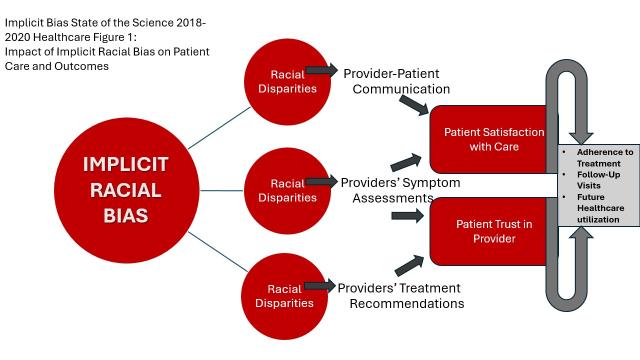

The Kirwan Institute has a long history of aggregating and disseminating the latest research developments regarding implicit racial bias. We remain steadfast in our commitment to rigorously curating and making this work accessible as part of our land grant mission. In honor of Kirwan’s 20th anniversary and the 10th anniversary of the first Kirwan State of the Science, we are releasing three (3) State of the Science reports simultaneously (2018, 2019, and 2020) in a new virtual format. We will chronicle research developments in three general domains: education, healthcare, and law/criminal justice over this three-year period. Prior State of the Science reports are cited and linked where applicable throughout this page.

Introduction to State of the Science 2018-2020

Introduction to State of the Science 2018-2020The period from 2018 to 2020 was a memorable phase in our collective history, marked by profound cultural moments of change and awareness. These years witnessed racial and ethnic upheavals on an unprecedented scale, some of which were fueled and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, notably exemplified by instances of racism directed towards African American and Asian communities. In addition, long-standing systemic racial disparities were illuminated and intensified, culminating in widespread protests and demands for justice in 2020.

Perhaps the most searing reminder of these injustices was the death of George Floyd, a Black man, under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer. This disturbing incident, virtually witnessed by millions across the globe through social media and news outlets, sparked a profound sense of moral outrage. The event led to a flood of marches and demonstrations, transcending borders as communities around the world rallied together in solidarity around the anthem of “Black Lives Matter.” This international call for justice highlighted the universal resonance of George Floyd’s eulogy: “What happened to Mr. Floyd happens every day in this country, in education, in health services, and in every area of American life” (Sharpton, 2020).

This poignant statement, alongside the countless other incidents of racial injustice that took place during the 2018-2020 period, underscores the critical necessity of studying and addressing implicit bias against racial and ethnic minority groups. Using this lens empowers us to further understand how unconscious prejudices permeate our societies and contribute to negative outcomes for these populations. It is only through a deeper understanding that we can devise effective interventions that potentially reduce or effectively limit the impact of such biases.

Although the format of this State of the Science has changed, its aim has not: we reviewed and analyzed findings related to implicit racial biases research conducted in this three-year period to inform current dialogues and inspire further research that might help rectify the ongoing racial disparities illuminated throughout this review. While empirical research on implicit bias attends to a wide variety of demographic categories, this report follows Kirwan’s mission and standard practice of examining publications that pertain to implicit racial or ethnic bias. The purpose of this introduction is to provide a systematic review of the scholarly social science literature pertaining to the foundations of racial and ethnic implicit bias, which includes its definition, uses, and methodologies employed for empirical measurement of the phenomenon. Separate sections track research published in 2018, 2019, and 2020 across the domains of education, healthcare, and law/criminal justice.

Kirwan’s Approach to Defining Race and Ethnicity

The racial and ethnic classifications utilized in Kirwan’s 2018-2020 State of the Science reports adhere to the guidelines established by the 1997 Office of Management and Budget (OMB, 1997). It is also important to acknowledge that approaches to defining racial or ethnic categories have shifted and changed over time. For example, the US Census has allowed respondents to mark more than one racial category in the 2000, 2010 and 2020 census efforts, which was previously forbidden. Our approach to reviewing the scholarship published from 2018-2020 utilizes the OMB and Census approaches that were applicable during this timeframe. As aggregators of the research, we cannot control the racial and ethnic classifications employed by the original authors. This means not all racial and ethnic groups are studied or mentioned in recent publications, which itself is a research finding that emerges from this effort. That said, we are committed to ensuring consistency and coherence in the terminology used throughout our reports to enhance reader comprehension and facilitate a more accessible reading experience.

American Indian or Alaskan Native. An individual who has origins in any of the indigenous peoples of North America and South America (including Central America) and maintains their cultural identity through tribal associations or attachment with their community.

Asian. An individual with origins in any of the original populations of the Far East and Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for instance, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Black. An individual with origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa.

Hispanic or Latino. An individual with a cultural or ancestral background linked to Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, Central or South American, or other Spanish culture or origin, irrespective of their race.

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. An individual having origins in any of the indigenous peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

White. An individual with origins connected to the original peoples of Europe, North Africa, or the Middle East.

Key Definitions and Concepts

Implicit bias is defined as the set of attitudes or stereotypes that affect our cognition, affect and behavior in unconscious and automatic manner (Blair, 2002; Rudman, 2004). Implicit biases can be either positive or negative, and are activated involuntarily without an individual’s intention, awareness, or control. Implicit biases are pervasive; every individual is susceptible to them, including children and those with avowed commitments to impartiality (Nosek et al., 2007; Rutland et al., 2005; Greenwald et al., 1998; Kang et al., 2011).

Both nature and nurture contribute to how our implicit biases are formed. Renowned scholar Jerry Kang contends that, “even if nature provides the broad cognitive canvas, nurture paints the detailed pictures – regarding who is inside and outside, what attributes they have, and who counts as friend or foe” (Kang, 2012, p. 134). Indeed, our implicit biases are often developed as a result of mental associations formed by the direct and indirect messages we receive from our social environment, including those from parents, siblings, school environment, and the media. These messages are often about different groups of people, where certain identity groups are paired with certain characteristics (Nosek et al., 2007). For example a long line of research has documented media programming excessively portrays Blacks as criminals (e.g., Dixon & Linz, 2000; Gilens 2000; Gilliam 2000). After constantly being exposed to such messages, we may begin to associate a group unconsciously and automatically with certain characteristics, regardless of whether these associations actually reflect the truth of reality (Hancock 2004; Mendelberg 2001; Winter 2008). Implicit forms of bias also differ from more explicit forms, such as beliefs and preferences, which individuals are generally consciously aware of and can, if they choose to, identify and communicate to others (Daumeyer et al., 2019; Dovidio & Gaertner, 2010).

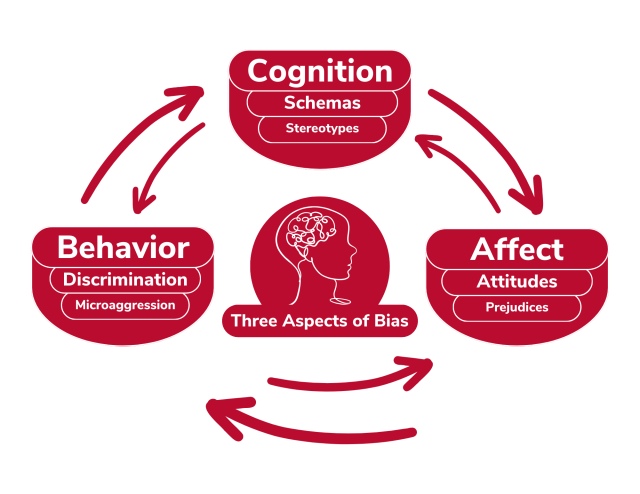

There are a few key types of mental associations that are frequently studied in conjunction with implicit bias. Infographic below illustrates both how they relate to each other and how they relate to implicit bias. Where it’s helpful we also provide some examples of each concept.

- Schemas can be described as mental frameworks that represent one’s understanding of an object, person, or situation, encompassing knowledge of its attributes and the connections between those attributes (Manstead et al., 1995). These mental structures are abstract, capturing common elements across various instances and serve to simply the complexities of reality. Schemas serve primarily as a guide for processing new information by setting up expectations about the type of information that will follow, linking specific details of a stimulus to a broader concept, and filling in any gaps in our understanding. There are five (5) primary types of schemas: person schemas (e.g., what a figure skater looks like), self-schemas (e.g., I am adventurous and outgoing), role schemas (e.g., nurses are caring), event schemas or scripts (e.g., going to a restaurant involves the sequence of reading the menu, ordering, eating and then paying the bill), and content-free schemas that contain information process rules instead of specific content (e.g., you never trust what your cousin says, regardless of what they actually say).

- Stereotypes are societally shared beliefs or abstract mental representations that we associate with social groups and their members (Blair, 2002; Greenwald & Krieger, 2006; Manstead et al., 1995) regardless of whether they are factually accurate. Stereotypes are sometimes described as “group schemas” or “group prototypes.” For example, Asians are commonly stereotyped as being proficient in math, while the elderly are often stereotyped as being feeble. Regardless of the valence (i.e., positive, neutral, or negative), these associations generally can be automatically accessed because they are routinized in our lives (Rudman, 2004). It is worth noting again here that stereotypes are not necessarily empirically valid and may reflect associations that we would consciously disapprove of (Reskin, 2005).

- Attitudes refer to psychological tendencies that involve the evaluation of a specific object or entity (Manstead et al., 1995). These evaluative feelings can range from having a positive, negative, or neutral stance towards a subject. Attitudes are often influenced by a person's beliefs, experiences, and values as well as factors like culture, social norms, and media representations. Importantly attitudes can change over time as people encounter new experiences or receive new information (Greenwald & Krieger, 2006; Kang, 2009).

- Prejudices are defined as antipathies “based upon a faulty and inflexible generalization” (Allport, 1954, p.9). Notably this key concept includes actions and not simply mental representations. Prejudice is characterized as holding derogatory attitudes or beliefs, expressing negative affect, or displaying hostile or discriminatory behavior toward an individual based on their group membership, which is associated with negative attributes assigned by the perceiver (Manstead et al., 1995). Prejudice has three components: a cognitive aspect involving beliefs about a particular group, an affective aspect involving feelings of dislike, and a conative aspect involving a behavioral inclination to exhibit negative actions or behaviors towards the targeted group (Dovidio et al., 2010).

- Microaggressions refer to subtle insults, either verbal, non-verbal, and/or visual, directed toward individuals or groups. Microaggressions are often automatic and unconscious (Solorzano et al., 2000). Put simply, they are brief, everyday exchanges that convey derogatory messages to people due to their membership in a minority group. These microaggressions are often delivered unconsciously through subtle snubs, dismissive looks, gestures, and tones during daily conversations and interactions. Despite their frequency, they are often dismissed or overlooked as being harmless. However, it is crucial to recognize that microaggressions have a detrimental impact on people of color. They diminish their performance in various settings by depleting their psychic and spiritual energy and creating inequalities (Sue et al., 2008).

We acknowledge the nuanced differences among these key concepts not least because the research we aggregated also acknowledged these differences. For example, Phills and colleagues (2020) examined the bidirectional causal relationship between implicit stereotypes and implicit prejudice. They found that valence changes in implicit stereotype (measured as semantic attributes associated with a group) influence in implicit prejudice. Moreover changes in implicit prejudice, defined as the valence (positive/negative) associated with the group, can also influence the extent to which it is associated with positive or negative semantic attributes. In other words, the two constructs are causally related concepts. In order to enhance simplicity and improve reader comprehension, the term “implicit bias” will be employed as a comprehensive label when evaluating articles that explore the impact of attitudes, stereotypes, prejudice, or schemas on our understanding, behaviors, and decision-making in an unconscious and automatic manner. We provide citations of the relevant research so that interested readers can go back to the original research for more detailed information.

How Did They Do That?

“To gain a better understanding of the appropriateness of using the term implicit bias as an overarching concept, a preliminary examination of the literature was conducted by two researchers, independently. While it was not a formal intercoder reliability check, this informal assessment aimed to evaluate the alignment between the articles selected for review and the definition of implicit bias provided earlier. Each researcher independently reviewed the same subset of 30 articles that did not explicitly employ the term “implicit bias,” from the overall pool of 291 articles. A consensus was reached through discussion to determine the criteria for identifying articles to be included in the review. Based on the established criteria, one of the researchers subsequently reviewed the remaining articles and made informed decisions regarding their inclusion in the review.”

Article Selection Strategy

Two rounds of literature searches were conducted for this report series covering articles in the English language published from January 2018 to December 2020. The search terms used were “unconscious,” “implicit,” “prejudice,” “bias,” and “stereotyp*” in combination with “rac*,” “ethni*,” and “color.” Three reviewers independently screened and selected eligible studies based on the title and abstract. Subsequently, the selected articles were re-evaluated by reading them in their entirety and categorized based on discipline. The inclusion criteria for the articles were as follows: 1) the articles should contain at least one finding or conceptual discussion related to implicit bias based on race or ethnicity; 2) peer-reviewed journal articles were given priority. Special cases such as articles from law journals, credible open-access journals and conference proceedings were also included. During manuscript preparation two members of the research team also performed an informal assessment that aimed to evaluate the alignment between the articles selected for review and the definition of implicit bias we discussed above. Subsequently, we verified whether the articles selected for discussion in these manuscripts a) substantively discussed implicit bias; b) fit within one of three categories – education, healthcare, or law/justice; and c) were academic articles published in either peer-reviewed or other academic journals. In sum, we analyzed a total of 133 articles; each subject report details the number of articles published between 2018 and 2020.

Empirical Measurement of Implicit Bias

The year 2020 marked the 25th anniversary of seminal publications that laid the foundation for measuring implicit biases. Over the past couple of decades, at least 20 different instruments (see Table 1) have been developed to measure implicit bias, beginning with Fazio and colleagues (1995), who validated the evaluative priming task (EPT). In the same year, Greenwald and Banaji’s (1995) reviewed implicit social cognition research, which served as the basis for the development of the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 1998). In the upcoming sections, we will provide a concise introduction to these two widely used measures of implicit bias. Although the EPT and the IAT have been the key instruments driving the upswing of research with implicit measures, they have distinct conceptual underpinnings (Payne & Gawronski, 2010). We will also briefly review other commonly employed measures that have been developed based on the foundation laid by the EPT and the IAT, including some physiological measures that have also been utilized to assess implicit bias.

Currently Available Implicit Measures as Summarized by Gawronski et al., 2020

| # | Measurement Instrument | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Action Interference Paradigm | Banse et al. (2010) |

| 2 | Affect Misattribution Procedure | Payne et al. (2005) |

| 3 | Approach-Avoidance Task | Chen & Bargh (1999) |

| 4 | Brief Implicit Association Test | Sriram & Greenwald (2009) |

| 5 | Evaluative Movement Assessment | Brendl et al. (2005) |

| 6 | Evaluative Priming Task | Fazio et al. (1995) |

| 7 | Extrinsic Affective Simon Task | De Houwer (2003) |

| 8 | Go/No-go Association Task | Nosek & Banaji (2001) |

| 9 | Identification Extrinsic Affective Simon Task | De Houwer & De Bruycker (2007) |

| 10 | Implicit Association Procedure | Schnabel et al. (2006) |

| 11 | Implicit Association Test | Greenwald et al. (1998) |

| 12 | Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure | Barnes-Holmes et al. (2010) |

| 13 | Recoding Free Implicit Association Test | Rothermund et al. (2009) |

| 14 | Relational Responding Task | De Houwer et al. (2015) |

| 15 | Semantic Priming (Lexical Decision Task) | Wittenbrink et al. (1997) |

| 16 | Semantic Priming (Semantic Decision Task) | Banaji & Hardin (1996) |

| 17 | Single Attribute Implicit Association Test | Penke et al. (2006) |

| 18 | Single Block Implicit Association Test | Teige-Mocigemba et al. (2008) |

| 19 | Single Category Implicit Association Test | Karpinski & Steinman (2006) |

| 20 | Sorting Paired Features Task | Bar-Anan et al. (2009) |

| 21 | Truth Misattribution Procedure | Cummins & De Houwer (2019) |

Note. From Gawronski, B., De Houwer, J., & Sherman, J. W. (2020). Twenty-five years research using implicit measures. Social Cognition, 38(Supplement), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2020.38.supp.s1

In general, many researchers have concluded that implicit and explicit measures capture distinct but related mental constructs (Nosek et al., 2007). The primary difference between implicit bias and other forms of bias revolves around the degree of consciousness. Explicit biases can be consciously registered and reported (Amodio & Mendoza, 2010). Implicit biases, however, arise outside of one’s conscious awareness and are not always congruent with an individual’s consciously held beliefs or attitudes (Graham & Lowery, 2004; Kang et al., 2012; Reskin, 2005). They may not necessarily reflect stances that one would explicitly endorse. While implicit and explicit bias are distinct concepts, they share similar impact: both mental constructs affect one’s actions, decisions and understanding.

In attempts to understand the differences between implicit and explicit bias, a number of other moderating factors have been identified to explain the divergent results captured by implicit and explicit measures (Rudman, 2004), including motivation to report explicit attitudes that correspond to one’s implicit attitudes (Dunton & Fazio, 1997; Fazio et al., 1995; Nier, 2005), the psychometric properties of the specific measurement techniques (Cunningham et al., 2001; Greenwald et al., 2003) and social desirability concerns (Dunton & Fazio, 1997; Nier, 2005; Nosek & Banaji, 2002).

Rudman’s (2004) work elucidates five factors that are more likely to influence the development of implicit biases than explicit ones. The first factor pertains to early experiences that may lay the foundation for our implicit attitudes, whereas explicit attitudes are influenced more by recent events. Furthermore, affective experiences tend to have more impact on implicit orientations than self-reports. She also listed cultural biases and balance principles as key factors that shape implicit biases. While the above-mentioned four factors were already established in the literature, Rudman adds a fifth factor for consideration, namely the self. According to Rudman (2004), it may be challenging to have implicit associations that are detached from the self, whereas controlled evaluations may enable more objective responses. If the self is a primary cause of implicit orientations, it is likely because individuals tend not to view themselves impartially, and this partisanship can then shape evaluations of other objects that are (or are not) related to the self.

The difficulties associated with measuring implicit bias arise in part due to its automatic and unconscious nature. Conventional self-report measures of bias rely on introspective and conscious reports regarding one's experiences and beliefs, which are indirect methods for assessing implicit bias. Additionally, impression management, or social desirability concerns, can undermine the validity of self-report measures. It is of particular concern when the target of measure is related to bias, as the desire to be perceived positively can lead people to alter their self-reported beliefs and attitudes to appear more impartial (Amodio & Devine, 2009; Dovidio et al., 1997; Fazio et al., 1995; Greenwald & Nosek, 2001; Greenwald et al., 2009; Nier, 2005; Nosek et al., 2007). This inclination towards impression management can compromise the validity of self-reports, especially when they are questioned on socially or politically sensitive issues such as intergroup or interracial behaviors (Dovidio et al., 2009; Greenwald & Nosek, 2001; Greenwald et al., 2009). Due to these limitations, self-reports are generally considered insufficient for capturing all dimensions of individual prejudice (Tinkler, 2012).

The Evaluative Priming Task (EPT)

The development of the EPT was guided by the notion that attitudes are represented in memory as associations of varying strength for object evaluation (Fazio, 2007). This view suggests that encountering an attitude object may automatically activate its associated evaluation via the spread of activation to the extent that the association between the two is sufficiently robust. For example, Fazio et al. (1995) conducted a study that explored the effects of priming participants with photographs of black and white undergraduates. During the study, participants were presented with an evaluative adjective, such as “pleasant” or “awful,” and their primary task was to indicate the connotation of the adjective as quickly as possible. A photo was briefly presented prior to each target adjective, with participants instructed to attend to the faces for later identification. The study was presented to participants as a cover story in which judgment of word meaning was portrayed as an automatic skill that should not be disturbed by the additional task. The results of this study indicated that Black and White faces had different effects on participants’ response time in indicating the connotation of the target adjective. Compared to white faces, black faces facilitated the response to negative adjectives and disrupted the response to positive adjectives. This pattern suggested that, on average, negativity was automatically activated by the black primes (Fazio& Olson, 2003). In this vein, the EPT was seen as an “unobtrusive” measure of attitudes, capturing unintended expressions of attitudes that are difficult to regulate, or that individuals may be unwilling to reveal on explicit self-report measures (Gawronski et al., 2020).

The Implicit Association Task (IAT)

Unlike the focus on unintentional expressions of attitudes that are challenging to regulate, the creation of the IAT was guided by studies on implicit memory. This approach proposed that memories of past experiences could impact responses even when they were inaccessible to introspection (Gawronski et al., 2020). In practice, the IAT gauges the degree of association between a target concept and an attribute dimension by measuring the time it takes for participants to utilize two response keys, each with a dual meaning. The participants’ task is to classify stimuli as they appear on the screen, such as categorizing names (e.g., “Latonya” or “Betsy”) as typical of blacks or whites. For example, race is the target concept, and the keys are labeled “black” and “white” in Greenwald et al.’s (1998) IAT on racial attitudes. Participants then categorize a range of words with clearly valenced meanings (e.g., “poison” or “gift”) as pleasant or unpleasant, which constitutes the attribute dimension.

During the critical phase of the study, the two categorization tasks are combined. Participants perform this combined task twice - once with one response key signifying Black/pleasant and the other labeled White/unpleasant, and once with one key indicating Black/unpleasant and the other White/pleasant - in a counterbalanced order. The main question is which response mapping participants find easier to use. In the Greenwald et al. (1998) study, participants were much quicker at responding when Black was paired with unpleasant than when Black was paired with pleasant. On average, participants found it easier to associate the target concept Black with the attribute unpleasant than with the attribute pleasant, which can be interpreted as indication of implicit racial bias.

Over the past decades, at least 20 different instruments (see Table 1) have been developed to measure implicit bias. Among these instruments, the IAT (#11) and the Single Category Implicit Association Test (SC-IAT; #19) are the most common measures used for the assessment of implicit biases and self-concepts. Most recently the IAT was found to have a higher accuracy of predicting behavioral choices over the SC-IAT, regardless of the scoring procedure (Epifania et al., 2020).

Additional implicit measures have been developed based on the groundwork laid by the EPT and the IAT. Two noteworthy examples include the Extrinsic Affective Simon Task and the Go/No-Go Association task. The former was developed as an affective variation of the spatial Simon task to measure attitudes implicitly (De Houwer & Eelen, 1998; De Houwer, 2003). During this task, participants must discriminate between the stimuli (e.g., noun/adjective or man-made/natural) by responding “positive” for one category and “negative” for the other. As the stimuli themselves have varying levels of associated valence, this process produces both evaluatively congruent trials, where the stimulus’s valence and its related category signal the same response (e.g., responding “positive” to “flower” as it is a noun), and evaluatively incongruent trials, where response competition arises (e.g., responding “negative” to “happy” as it is an adjective). The Go/No-Go Association Task was introduced by Nosek & Banaji (2001). It is a modified version of the IAT that eliminates the need for a contrast category. During the task, participants react to stimuli that symbolize the target and attribute categories as “good,” but take no action in response to other stimuli. The time taken to respond, or any errors made, are then compared to a block of trials where participants must respond to items that represent the target category and “bad.”

Several physiological methods have also been used as implicit measures of implicit bias. These diverse approaches share a common goal: to estimate the construct of interest without requiring a verbal self-report from the participant. The primary advantage of these indirect estimates is that they are less likely to be influenced by social desirability concerns. In many cases, participants may not even be aware that their attitudes, stereotypes, and so on are being measured until after a “debrief” session with the researchers, which is a common strategy used to make sure that accurate results are obtained while preserving the ethical standards of conducting human subjects research that informs participants of their rights and preserves said rights.

The seminal research in a related field experimented with a variety of physiological measures. Vanman et al. (2004) employed facial electromyography (EMG) to investigate racial prejudice. Both Phelps et al. (2000) and Hart et al. (2000) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study amygdala activation as an indicator of racial evaluation. Eyeblink startle response to Black and White faces has also been used for this purpose (Phelps et al. 2000, Amodio et al. 2003). Cardiovascular reactivity measures, indicating challenge or threat, have been utilized to examine responses to interactions with Black individuals and others who face stigma (Blascovich et al. 2001). Furthermore, Cacioppo and colleagues have applied event-related brain potentials as a real-time measure of categorizing stimuli as positive or negative (e.g., Cacioppo et al. 1993, Crites et al. 1995, Ito & Cacioppo, 2000).

While these physical measures can effectively identify involuntary responses to stimuli, they also present challenges to implement, unlike the more broadly accessible online tests. The utilization of psychophysiological measures can demand significant time, infrastructure, and money. Therefore, these strategies may not be readily accessible to all researchers. When selecting an appropriate implicit bias measurement tool, we recommend a careful review of the strengths and drawbacks of each measure, including attention to the target concept of interest (e.g., stereotypes, schema, attitudes) to make informed decisions regarding the most suitable measure for their specific research/training objectives.

Facial Electromyography (EMG)

A technique used in the field of psychophysiology that measures the electrical activity produced by muscles in the face. This technique is valuable for examining implicit bias conveyed through emotional expressions. For example, EMG can be recorded from sites corresponding to muscles used in smiling, which is an indicator of positive emotions. In a study that looked at the preferences of White college students when choosing hypothetical candidates for a fellowship, participants exhibited higher levels of EMG activity in their cheek muscles when viewing pictures of White applicants compared to Black applicants. Elevated cheek EMG activity signals more positive emotions, suggesting that the participants may have an implicit bias in favor for White applicants (Vanman et al., 2004).

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

A specialized technique that measures and maps the brain’s activity. When a brain region is more active, it consumes more oxygen, leading to a series of hemodynamic responses that fMRI can capture and visualize. Based on this mechanism, fMRI focuses on measuring changes in blood flow to particular areas of the brain as an indicator of increased neural activity. This allows researchers to understand how different cognitive tasks or stimuli engage specific brain regions. For example, activation in the amygdala, a small structure in the medial temporal lobe known for emotional learning and memory, has been linked to racial evaluation. Phelps and colleagues (2000) found that activation in the left amygdala is correlated with implicit bias shown through the IAT reaction time measure.

Pervasiveness of Implicit Racial Bias

Implicit racial bias has been found across different racial groups (Nosek et al., 2007) across a wide variety of countries. Nosek and colleagues were the first to conduct a large-sample study on the pervasiveness of implicit racial biases. Based on the data gathered from over 2.5 million IATs and self-reported surveys between 2000 and 2006, they found that about 68% of participants exhibited implicit racial bias against Black/dark-skin individuals, and 14% exhibited the reverse. It is worth noting that Black participants were the only group that, on average, did not show an implicit preference for White individuals. When examined by racial group, White participants displayed the strongest implicit pro-White preference. American Indians, Asians, Hispanics, members of multi-racial groups, and those who identified as “other” also displayed similar implicit racial preference at medium to large levels (Nosek et al., 2007). Nosek and colleagues also examined implicit associations of Blacks and Whites with weapons and harmless objects (e.g., umbrella, keys, or toothbrush). Approximately 72% of the sample showed strong associations of Black individuals with weapons and White individuals with harmless objects. While evidence of implicit bias associating Blacks with weapons was comparatively weaker among Black participants in comparison to other racial groups, the effect was still notable and relatively strong according to conventional effect size standards.

The target of negative implicit racial bias is not limited to Blacks. Two IAT instruments were designed to measure the implicit associations of ethnic-national groups. Specifically, they focus on determining whether Asian Americans or native Americans are more easily associated with the attribute of Foreign versus White Americans with American. Nosek and colleagues (2007) found that, on average, participants demonstrated a higher ease in associating White faces with the concept of “American,” and Asian or Native American faces with the notion of “Foreign,” rather than the reverse. This association, referred to as the Asian stereotype, was observed in 61% of the sample, while the Native American stereotype was observed in 57% of the sample.

When using the IAT instrument, Nosek and colleagues (2007) found that this measure detected stronger bias in people than the self-report measures. Specifically, they used a statistic called “Cohen’s d” to measure how far from a “neutral” standpoint people’s racial attitudes were in their nationally representative sample. While explicit self-report measures showed that people only had a small to medium level of preference for White (d = 0.31), the race attitude IAT for the same respondents revealed a much higher level of implicit preference for White (d = 0.86, more than twice the self-report score). If we were to translate these findings into a “normal” statistical distribution, we would predict that as many as 54.4% of individuals may explicitly admit to having a preference for White individuals. However, Nosek and colleagues’ empirical findings document a substantially larger proportion, 74.5%, who actually hold this preference for White individuals at an implicit level.

Mitigation Strategies for Implicit Bias

Although there was widespread belief prior to 2000 that implicit biases were difficult to change (Greenwald & Lai, 2020), there are findings showing that the unconscious attitudes or stereotypes we have formed can be “unlearned.” This means that implicit biases are malleable and can be replaced with new mental associations through interventional efforts (Blair et al., 2001; Blair, 2002; Dasgupta & Greenwald, 2001; Dasgupta, 2013; Roos et al., 2013). Such findings are important for providing support particularly to those individuals who might score on an EPT or IAT as having a biased preference but who do not think of themselves as biased or racist. We review general findings here; we also chronicle documented mitigation strategies pertaining to each subject category (education, healthcare, law/criminal justice) at the end of each State of the Science report.

Research on racial attitudes conducted by Fazio and colleagues has identified three distinct types of individuals, characterized by the automatic processes they engage in and their subsequent efforts to counter or control those evaluations (Fazio et al., 1995). The first group consists of individuals who are non-prejudiced; these individuals do not exhibit the activation of negative attitudes towards a particular racial group. The second group encompasses individuals who are genuinely prejudiced, as they experience negative automatic associations but make no attempts to counter or control the expression of those associations. The third group comprises individuals who may experience negative automatic associations, but they are motivated to actively counter such sentiments. Individuals in this last group, who seek to mitigate the role of implicit racial biases in their overt actions or behaviors can pursue intentional actions at either the personal (internal) or the situational (external) level. Each type of influence has been documented to shape the conditions under which implicit racial biases are likely to affect behavior.

Personal Factor 1: The Role of Motivation

Motivated individuals have the capacity to exert influence over the automatic operation of stereotypes and biases (Blair, 2002). Dunton and Fazio (1997) investigated the influence of motivation on controlling biased reactions and identified two sources of motivation: a concern with appearing prejudiced and a desire to avoid conflicts or disagreements about one’s thoughts or positions. Their findings suggested that individuals with low motivation to control biased reactions were more likely to provide accurate self-reports of racial attitudes. Devine et al. (2002) further explored the impact of motivation on implicit and explicit biases, concluding that explicit biases were moderated by internal motivation, while implicit biases were influenced by the interaction of both internal and external motivation.

Devine et al.’s finding is consonant with that of Irene Blair. Blair (2002) identified two individual (internal) level interventions and one situational (external) intervention that can potentially mitigate implicit bias. The internal factors involve examining the manipulations of the perceiver’s motivations, goals, and strategies during the process in which implicit bias arises. On the other hand, the external factor identified by Blair focuses on changes in the context surrounding the stimulus or variations in the attributes of group members.

Individuals who possess high motivation have the ability to influence the automatic activation of stereotypes and bias (Blair, 2002). When an individual’s self-image is threatened, they may automatically activate negative stereotypes in order to enhance their own appearance or discredit someone they dislike (Sinclair & Kunda, 1999; Spencer et al., 1998). Conversely, they can also automatically suppress negative stereotypes and activate positive ones when it benefits their self-image (Sinclair & Kunda, 1999). Automatic stereotypes and bias can be influenced by the social demands of a situation and the nature of one’s relationship with others. For example, White individuals may moderate their automatic bias when interacting with a Black person, particularly if they are in a subordinate position (Lowery et al., 2001; Richeson & Ambady, 2001). They may also adjust their automatic stereotypes if those stereotypes conflict with social norms (Sechrist et al., 2001).

The concept of overcorrection, where individuals compensate for their biases by displaying exaggeratedly positive or negative responses that conceal their true attitudes, has also been investigated. Dunton and Fazio (1997) suggested that highly motivated individuals who aim to control prejudiced reactions might overcompensate for their automatically activated negativity, resulting in more positive judgments than those with activated positivity.

Personal Factor 2: Promotion of Counter Stereotypes

It is argued that individuals who perceive stereotypes have the ability to actively foster counter-stereotypic associations. By doing so, they can potentially undermine the influence of implicit stereotypes in the process of information processing. Promotion of counter stereotypes can be achieved through tasks such as priming of counterstereotype expectancy, mental imagery, and exposure to counterstereotypic group members (Blair & Banaji, 1996; Blair et al., 2001; Dasgupta & Greenwald, 2001). To examine the effect of counterstereotype expectancy on implicit bias, Irene Blair and Mahzarin Banaji (1996) conducted a sequential priming task, which assesses automatic associations by measuring how a briefly presented stimulus (prime) influences the response time to a subsequent stimulus (target). Half of the participants were instructed to anticipate prime-target trials that aligned with stereotypes, while the other half were informed to expect counterstereotypic trials. However, in reality, all participants experienced both stereotypic and counterstereotypic trials, with the anticipated trial type appearing only 63% of the time. The results of this study revealed that the counterstereotype expectancy significantly lowered levels of automatic stereotypes than the stereotype expectancy.

The effect of mental imagery was examined through tests targeting implicit gender stereotypes. Blair and colleagues (2001) instructed the participants to spend around 5 minutes to create a mental image of a strong woman, which is counterstereotypic to the traditional stereotype, and then complete an automatic gender stereotype test. Participants who engaged in the counterstereotypic mental imagery exhibited substantially weaker automatic stereotypes compared to participants in the control groups, which included those who attempted to suppress their stereotypes on their own.

The exposure-to-counterstereotypic-group-members mitigation strategy takes a somewhat different approach. A group of participants were exposed to either a) admired African Americans and disliked White Americans, b) disliked African Americans and admired White Americans, or c) nonracial control stimuli. Following the exposure, the participants took IAT automatic racial bias measures both immediately and 24 hours later (Dasgupta & Greenwald, 2001). The study found that exposure to positive Black group members reduced automatic bias against Blacks compared to exposure to negative group members or to control stimuli. It is also worth noting that this effect continued to be significant after 24 hours. While Dasgupta and Greenwald (2001) believe that this effect is likely to diminish after an extended hiatus, these findings remain significant as they challenge the assumption that automatic racial attitudes, ingrained through long-term socialization, are unchangeable.

One potential concern the researchers emphasized about their results regards the possibility that when individuals are exposed to strongly positive and negative exemplars of a particular stereotype, they might categorize these exemplars as “exceptions to the rule” and adjust their attitudinal response accordingly before expressing it. This observation aligns with studies on stereotypic belief revisions, which demonstrate that when confronted with evidence, explicitly held stereotypes can remain firm if the new evidence or exemplars are perceived as atypical (Bodenhausen et al., 1995; Kunda & Oleson, 1995; Rothbart & John, 1985; Weber & Crocker, 1983). As such, instead of revising the original stereotype, new cognitive categories are created to accommodate these counterstereotypic exemplars, a phenomenon known as subtyping. However, Dasgupta and Greenwald (2001) contend that this effect is less likely to manifest when individuals do not have ample cognitive resources to reflect on and recategorize these counterstereotypic exemplars. This perspective is supported by the findings of Dasgupta and Greenwald’s study, where exposure to counterstereotypes reduced implicit, but not explicit, stereotypes against Black individuals. The researchers therefore cautioned that care must be taken to ensure that this type of exposure doesn’t label the counterstereotypic exemplars as mere exceptions, which would inadvertently perpetuate the original stereotype.

Personal Factor 3: Group Membership and Identity

Perceptions of group membership and identity are another personal factor that can influence one’s implicit bias. Categories such as race, gender, and age can be perceived almost instantaneously (Cikara & Van Bavel, 2014; Ito & Bartholow, 2009). Ingroups, whether they exist in real life or are artificially created for an experiment, can result in attitudes and behaviors of favoritism (Pinter & Greenwald, 2011; vanKnippenberg & Amodio, 2014). Simon and Gutsell (2020) interrogated this phenomenon utilizing the minimal group paradigm developed by Tajfel, Billig, Bundy and Flament (1971). This paradigm allows researchers to create experimental social categories that participants have never encountered before, enabling control over individual experiences, motives, and opinions. Participants in this study were evenly assigned to two minimal groups with arbitrarily created racial names. Researchers found that knowledge of arbitrary group membership led participants to humanize and show implicit bias favoring their ingroup members of the minimal group, despite the cross-cutting presence of race. This finding demonstrates that even within minimal groups, the consequences of implicit racial bias can be overcome through recategorization.

To further comprehend the underlying dynamics of this effect, Fritzlen and colleagues (2020) conducted two studies exploring the boundary conditions of the reclassification effort. They first examined whether learning of an identity-implying similarity with an outgroup could influence once’s implicit bias towards that outgroup. One of the identity-implying similarities they used in the study was genetic overlap with an outgroup. Their first study found that White participants who were made to believe that they had greater than average genetic overlap with African Americans showed decreases in implicit bias against that racial group. In a follow-up study, the researchers explored whether this effect holds in the context of sexual orientation identity. In this study, heterosexual participants were led to believe that they exhibited same-sex attraction and their implicit bias against homosexual individuals were measured. The findings showed that heterosexual participants’ implicit biases against homosexual individuals were reduced only if respondents believed that sexual orientation was biologically determined. Thus, Fritzlen and colleagues (2020) concluded that learning of an identity-implying similarity with an outgroup can reduce implicit bias if that group membership is perceived as immutable.

These findings hint at a broader implication that aligns with the intergroup contact theory, which suggests that direct contact between members of different social or cultural groups can be effective in reducing prejudice and conflicts between groups (e.g., Allport & Kramer, 1946; Lee & Humphrey, 1968; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). For instance, Kephart (1957) found that White police officers in who had worked with Black colleagues differed substantially from other White policemen on the force. They had fewer objections to teaming with a Black partner and taking orders from qualified Black officers. Combined with the evidence for minimal group reclassification effect on implicit bias (Frizlen et al., 2020), this suggests that enhancing awareness of shared group membership or identities, even arbitrary ones, could serve as a strategic approach to fostering positive intergroup relations and reducing implicit biases.

Furthermore, having positive intergroup contact has been shown to have potential positive influence over implicit bias as well in both virtual and real-life settings. Early behavioral studies found that people are better at recognizing faces from their own race compared to faces from other racial targets (Meissner & Brigham, 2001), a phenomenon dubbed as “the own race bias.” Following this line of research, Farmer and colleagues (2020) investigated whether positive intergroup contact can moderate the implicit bias in face perception using fMRI. In their study, White participants with a varied range of contact experiences with Blacks were first selected through a pre-task questionnaire. During the fMRI scan the selected participants completed an individuation task (favorite vegetables) and a social categorization task (above or under 25 years old) while viewing the faces of both Black and White strangers. The fMRI results showed that more frequent positive contact with Black individuals increased activation for Black faces in the social categorization task. This finding shows that quality of intergroup contact is also a key factor in processing out-group faces and reducing the own-race face bias. Improving the quality of intergroup contact is something individuals who are motivated to mitigate their biases have control over in their personal lives.

Contextual Factor 1: Configuration of the Cues

One important area for mitigation efforts focuses on how individuals interpret cues provided to them. Two types of studies have ensued: impression formation and perspective taking. In the classic impression formation studies conducted by Asch (1946), participants were given the task of forming impressions of an individual based on a set of traits such as skillfulness, industriousness, and intelligence. The presence of the trait “warm” or “cold” on the list had a significant impact on the impressions formed by the participants, leading to notable differences in their evaluations. Researchers argued that such fluidity in meaning may also be observed in automatic processes such as implicit stereotypes and biases (Blair, 2002). For instance, Macrae et al. (1995) conducted a study that highlighted how even a slight contextual change can exert a notable influence on automatic stereotypes. In their experiments, all participants were exposed to a Chinese woman, and subsequent measurements of automatic stereotypes toward both Chinese individuals and women were taken using a lexical decision task. In one condition, the Chinese woman was observed applying makeup, while in another condition, she was seen using chopsticks. As hypothesized, Macrae et al. discovered that participants who witnessed the woman applying makeup exhibited faster responses to traits stereotypically associated with women and slower responses to traits stereotypically associated with Chinese individuals. Conversely, participants who observed her using chopsticks displayed the opposite pattern of responses. Despite the stimulus remaining the same, a minor alteration in the context resulted in a substantial change in the automatic stereotypes evoked by her presence. Similarly, the automatic attitudes triggered by the presence of the same Black individual can vary depending on the setting (Wittenbrink et al., 2001). For example, when a person is encountered on a city street, different automatic attitudes may emerge compared to when they are encountered inside a church. In general, city streets are often associated with more negative perceptions compared to the interior of a church, and similarly, Black faces tend to be perceived more negatively than White faces. It is important to note, however, that these qualities do not independently impact the automatic process. Instead, their effects are multiplicative, meaning that when a Black face is encountered in a city street context, the automatic negativity becomes particularly strong.

An individual’s capacity to take perspectives and to show empathic concerns are also significant predictors of their implicit bias (Patané et al., 2020). Researchers have theorized that bilingualism may enhance perspective-taking at early developmental stages, thus reducing the expression of social bias. Being raised with more than one native language is often considered an advantage as it diversifies the range of linguistic, social, and cultural experiences available to an individual (Singh et al., 2020). Singh and colleagues compared monolingual and bilingual children to examine whether bilingual individuals are as susceptible to racial bias as their monolingual counterparts. Results showed that bilingual individuals displayed less implicit bias against Blacks. Additionally, it is possible that bilingualism predisposes individuals to more frequent social encounters with outgroups (something we discussed in association with personal factor #2), which may also reduce implicit bias against members of an outgroup.

Kang and Falk (2020) explored perspective-taking via an fMRI study to investigate the relationship between individuals’ tendencies to engage brain regions that support perspective-taking and their implicit biases towards a stigmatized group. Their findings revealed that an intervention task that exercised one’s ability to make inferences about others’ mental states was able to reduce implicit bias. Therefore, the researchers argued that intervention strategies designed to enhance social cognitive processing could be effective in reducing people’s implicit biases against stigmatized individuals. Patané and colleagues explored a related perspective-taking question using immersive virtual reality (VR) technology to explore whether interventions tailored to increase perpective-taking can help to reduce implicit racial bias and the use of VR technology to design interventions to reduce implicit racial bias. The researchers had a group of White study participants embody a Black virtual body. They compared those who engaged in a cooperative activity with another Black avatar to those who engaged in a neutral activity. The results revealed that those who engaged in a cooperative activity with a Black avatar had lower IAT scores after the social interaction than those who engaged in a neutral activity with a Black avatar.

Collectively, these findings indicate that automatic perception relies on the configuration of various stimulus cues, and even small changes can lead to remarkably different outcomes. It highlights the sensitivity of automatic processes to contextual factors and the potential for subtle modifications to have a profound impact on perception (Blair, 2002).

Contextual Factor #2: Time

Time is a recognized factor that plays a role in decision-making and the ability of individuals to regulate their reactions. Studies have indicated that time pressures can create conditions in which implicit attitudes become evident, even when individuals make explicit efforts to control them (Kruglanski & Freund, 1983; Payne, 2006; Sanbonmatsu & Fazio, 1990). This suggests that under time constraints, implicit attitudes may manifest themselves despite individuals’ explicit attempts to exert control over them (Bertrand et al., 2005). This phenomenon could have important implications for professionals such as police officers and other authorities who must make split-second decisions in their line of work. For some of these professionals who already harbor implicit biases, making quick judgment may not necessarily alter their biases but rather make these biases evident through behavioral manifestations. Highlighting this, Payne (2005) conducted a study to examine participants’ implicit associations related to weapons and race. The findings revealed that individuals with more negative implicit attitudes towards Blacks exhibited a stronger bias associating weapon with them. In a subsequent analysis, Payne (2006) emphasized that a crucial component of intentional response control gets overshadowed when the focus is solely on automatic bias.

Rapid judgments do not alter individuals’ biases but instead allow these biases to manifest as overt behavioral errors when time is limited. For example, Gallo et al. (2013) found that the time pressure on a White referee before making a decision to punish a football player affected their level of discrimination against players who are foreign and non-White, signaling an increase in implicit racial bias. Time pressure also shapes medical decisions, potentially to the detriment of racial minority patients. Stepanikova (2012) found that when family physicians and general internists are under high time pressure, their implicit bias against Black and Hispanic patients results in less serious diagnoses for both groups and a reduced likelihood of specialist referrals for Black patients.

Contextual Factor #3: Cognitive “Busyness”

According to Reskin (2005), any factors that tax our attention, such as multiple demands, complex tasks, or time pressures, increase the likelihood of us resorting to stereotyping. Gilbert and Hixon (1991) investigated the influence of cognitive busyness on the activation and application of stereotypes. Their findings showed that cognitive busyness reduces the likelihood of stereotype activation. However, if a stereotype is activated, cognitive busyness increases the probability of applying that stereotype to the individual(s) in question. Payne (2006) conducted an experimental study to examine the relationship between bias and cognitive overload, a state in which an individual’s working memory is overwhelmed by more information or tasks than it can effectively handle at a given moment. Payne found that cognitive overload leads to increased bias, which he attributed to individuals’ diminished control over their responses due to lack of cognitive resources. Furthermore, Bertrand et al. (2005) identified three conditions conducive to the emergence of implicit bias, including lack of attention to a task, time constraints or cognitive overload and ambiguity. In the health care setting, cognitive load may stem from stressful mental tasks, such as decision-making for multiple patients, as well as environmental factors such as overcrowding. Supporting the perspective put forward by Bertrand et al., Johnson and colleagues (2016) found that overcrowding and patient load indeed contributed to increases in physicians’ implicit racial bias. Additionally, despite unfounded concerns about non-White individuals being more likely to abuse opioids, Burgess et al. (2014) reported that male physicians were less than half as likely to prescribe opioids for pain management to Black patients compared to White patients when under high cognitive load. Similar evidence was found in the field of sports as well. The ambiguity of situations regarding infringements in football was found to affect the referee’s level of discrimination, which strongly points to the influence of cognitive busyness on the presence of implicit bias (Gallo et al., 2013).

Conclusion

This introduction to the research on implicit bias has summarized more than 25 years of empirical research to define racial/ethnic implicit bias, outline contributing factors, and offer evidence-based mitigation strategies for individuals motivated to change. It dedicated a crucial amount of attention to this latter subject given this burgeoning area of research. Please explore the 2018-2020 State of the Science reports by subject domain below to review the research trajectories in your preferred topic of interest by clicking on the links below. Each domain features a segment dedicated to the advances in scholarship from 2018, 2019, and 2020, respectively.

Acknowledgements

The Kirwan Institute would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to various individuals who have contributed to the development and completion of this project. Earlier parts of this project began under the leadership of interim director Dr. Beverly J. Vandiver, who supervised literatures searches by Preston Osborn, MSW; Laura Goduni, MPH: and Xiaodan Hu, PhD during the challenging times of a global pandemic. Their work served as a trusted guide for this work.

Former Kirwan program coordinator Adriene Moetanalo provided literature classification checks and editing, which have greatly enhanced the quality of this report, as have the creative talents of Kirwan student worker Chi Mutiso, who designed the infographics that so effectively communicate the key terms, findings, and insights of this research.

Each of these individuals’ hard work enabled us to present a more informed analysis. They all played pivotal roles at critical points in the realization of this project, and for that we are incredibly thankful.

Implicit Bias in Education: 2018

Implicit Bias in Education: 2018In 2018, implicit racial bias research in education continued its expanded attention to the impact of implicit biases on students and education policy. Our review includes nine (9) studies published in 2018. Ranging from how educators’ unconscious stereotypes may lead to the dehumanization and marginalization of youth of color, to disparities in disciplinary actions and evaluations of learning skills, these studies provide an in-depth look at the pervasiveness of implicit bias in educational settings.

In educational settings, implicit bias has been well-documented in the literature as a contributing factor to differences in teacher-student interactions (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015; Warikoo et al., 2016). Beyond the classroom, however, implicit racial biases potentially held by school administrators, such as principals and vice principals who are also an integral part of education systems, are rarely examined. The impacts of implicit racial biases manifest students’ mental/behavioral/health and academic outcomes, as well as aggregated racial disparities in school discipline and underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minoritized populations across various academic fields. Understanding these biases, their manifestations, and impacts, can expand our ability to creatively address the persistent challenges implicit biases present in educational contexts.

Impact on Students

According to new research published in 2018, the detrimental effects of implicit racial biases on students can be classified into two subcategories: societal and institutional devaluation and negative academic outcomes. We take each in turn.

Prior research documents the ways in which implicit bias may lead to a dehumanization process where youth of color are perceived as older, less innocent, and therefore more accountable for their actions than their White peers of the same age (Goff et al., 2014). This dehumanization process could result in reduced or absent social protection in school settings, making children of color more susceptible to punitive measures and less likely to be given chances to rectify their wrongdoings (Goff et al., 2008). Building on the earlier work of Philip Goff (2008; 2014); Matteo Forgiarini and colleagues (2011); Joshua Correll and colleagues (2002); and Walter Gilliam and colleagues (2016), Annamma and Morrison (2018) argued that young individuals of color are subjected to the negative impacts of implicit bias through dehumanization, pain minimization, and fear maximization. Citing empirical evidence, Annamma and Morrison detailed in their discussion the process by which youth of color as young as 12-years old are dehumanized while their pain may be overlooked. The outcomes can be fatal for some, as seen in the case of Tamir Rice, who was shot by Cleveland police while playing with a toy gun. Meanwhile, others may endure less direct but still damaging forms of violence by adults in authority.

The role of fear maximization and dehumanization also affects subgroups of the United States population in particular ways. Anthony Brown (2018) offered a thorough review of theological, scientific, and social science discourses where the construction of race has been shaped in relation to Black males. The impact of these biased practices, according to Brown, originates from the durable racial discourses of power that persistently portray Black males as feared and dangerous. In this way Brown also emphasizes the connections between fear maximization, dehumanization, and implicit racial bias against Black males in schools and society.

A second area of 2018 research focuses on the impact of implicit racial biases upon teachers’ evaluations of students’ learning skills. Building on the prior work of Lennard Davis’s critical disability theory (2013), Parekh and colleagues (2018) argued that it is important to examine the role of implicit racial bias in teachers’ evaluations of students’ learning skills and how it affects different communities. They suggested that critical disability theory is particularly relevant because it dissects how our society’s excessive emphasis on ability can unfairly label people, especially those from communities that often struggle with poverty and precarity. Their exploratory study of teachers’ perception of students’ learning skills across demographic and institutional factors drew data from Canada’s largest public board of education, which served approximately 246,000 students at the time of the study. The researchers examined the associations between students’ self-reported racial identity and the degree to which they were noted as having “Excellent” learning skills across achievement categories. The findings indicated that White students were typically the most likely to be given this high rating for their learning skills. On the other hand, despite being compared at similar academic levels, students self-identifying as Black were less likely to be recognized as having “Excellent” learning skills. The results imply that Black students, irrespective of their academic performance, are not perceived to embody core attributes implicitly valued by the educational system.

This 2018 study aligns with similar results found at the post-secondary level in earlier research. In a simulated setting that replicated teaching interactions involving college student participants who exhibited lower performance on a test, researchers discovered that White instructors showed stronger implicit associations favoring White individuals and harbored negative associations towards similarly situated Black individuals (Jacoby-Senghor et al., 2015). Another study examined implicit racial associations held by teachers concerning White and Arab individuals in the United States (Kumar et al., 2015). It was observed that teachers with implicit biases favoring White individuals and holding negative associations towards Arab individuals were less inclined to establish a culturally responsive classroom environment and facilitate the resolution of interethnic conflicts within the classroom.

Historically both the intention and assumption of the roles that teachers play in classrooms have been focused on teachers’ ability to promote egalitarian attitudes and foster harmony among individuals of different races. Teachers – particularly but not exclusively White teachers – have been found to play a significant role in perpetuating racial inequality that requires attention, intention, and mitigation (Ladson-Billings, 1994; Gershenson et al. 2016). Please see the Mitigation Strategies section of this report for research findings regarding successful interventions.

Systemic Impact

Having explored the intricate ways in which implicit bias can directly impact student outcomes, we now investigate how these biases further manifest in specific areas of the educational system. In the education sector, the role of implicit bias has been linked to racial disparities in school disciplinary actions. Racial disparities play a significant role in both K-12 educational outcomes like high school graduation rates and youth getting caught up in what is now commonly called the “school-to-prison pipeline.” The stakes, therefore, could not be higher for young people.

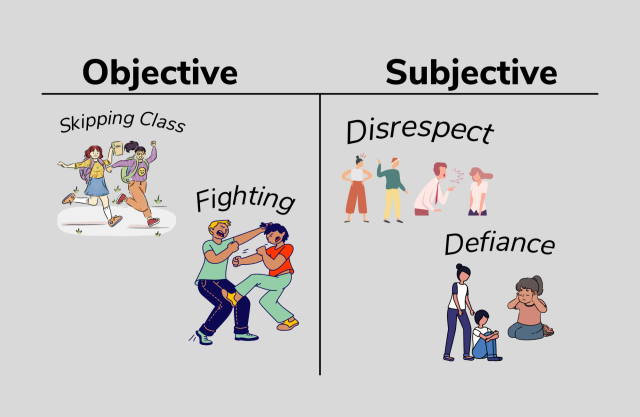

The first area of systemic implicit racial biases’ impact is school discipline. A vast amount of prior research suggests that disciplinary methods in schools affect students of color more than their peers (such as Wallace et al., 2008; Skiba et al., 2011; Hannon et al., 2013). A plethora of studies have found that certain student subgroups face a disproportionate amount of exclusionary discipline (Aud et al., 2011; Nowicki, 2018; U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2015). Implicit racial bias is one of the contributing factors to this problem (Girvan et al., 2017; Goff et al., 2014), particularly under certain conditions, such as when teachers or administrators are making decisions that are ambiguous, demand fast judgement, or when they are physically or mentally drained (Kouchaki & Smith, 2014). Black students were found to be significantly more likely than White students to be labeled as troublemakers, their misbehaviors were more likely to be perceived as indicative of a pattern. Educators also showed a higher tendency to envision themselves suspending a Black student in the future compared to a White student. (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015). The role of implicit bias in school discipline becomes more evident when we examine the disparities for more subjective behavior infractions such as disruption, as opposed to objective infractions like theft (Skiba et al., 2011). Objective infractions are behaviorally defined and based on objective event (e.g., fighting, skipping classes) that often leaves a permanent product, whereas subjective infractions are defined vaguely and more open to subjective interpretation (e.g., defiance, disrespect; Skiba et al., 2002; Theriot & Dupper, 2010). A study of student discipline records from more than 1,800 schools unveiled that these disparities were largely due to racial differences in office discipline referrals for subjectively defined behaviors such as defiance (Girvan et al., 2017). In sum, the past 12 years of studies reveal a troubling trend of systemic unfair treatment of students of color attributable to implicit racial bias.

A second area of systemic implicit racial biases’ impact is the persistent underrepresentation of racially minority students in particular fields, including but not limited to STEM education (McGee, 2021). Two 2018 studies – one in chemical engineering and one in the humanities – explored this impact, as did a cross-disciplinary study of recommendation letters. Farrell and Minerick (2018) examined the stealth nature of implicit bias in the realm of chemical engineering education. They argued that the pervasive presence of implicit bias and stereotype threat creates an environment where educators tend to allocate their time and resources to those students they perceive as more likely to succeed. Such an environment is likely to generate self-fulfilling prophecies and to negatively impact students’ interest in a subject as well as their levels of effort. In the same vein, Holroyd and Saul (2018) provided a detailed discussion of implicit bias in the field of philosophy. The authors suggested that implicit biases might be part of the explanation for the persisting underrepresentation and marginalization of multiple groups in philosophy. For instance, Black PhD students and professional philosophers combined are merely 1.32% of philosophers in the U.S. (Botts et al., 2014). The authors further emphasized the gravity of the situation, noting how implicit biases perpetuate unjust societal structures.

The role of implicit bias is not only limited to direct interactions between educators and students, but it also permeates more indirect aspects of the education system such as recommendation letters. Letters of recommendation, often utilized to evaluate undergraduate students’ potential for success as research assistants, interns, or graduate students, can sometimes include implicit bias, thereby potentially impacting decisions and constraining opportunities for underrepresented minorities and students from non-research institutions. Houser and Lemmons (2018) employed a text analysis software to analyze 457 recommendation letters for undergraduates applying for an international research experience, aiming to identify any significant difference in the language used to depict students who were accepted versus those who were rejected. The findings indicate that recommendation letters for successful applicants depict the students’ productivity with more certainty and incorporate more student work quotes. Conversely, the letters for unsuccessful applicants contain more positive emotion and mention the students’ insight, but also include more discrepancy-associated words (e.g., should) and tentative statements (e.g., perhaps, maybe). The statistically significant results showed the White students tended to be described in relation to their cognitive ability, insightfulness, productivity, and perceptiveness while non-White students tended to be depicted in affective languages and positive emotions.

Taken together, research conducted in 2018 regarding the impact of implicit bias continues to document the deleterious effects of implicit racial bias on students of color as well as an aggregate impact that produces systemic racial disparities. Highlights from 2018 include a theoretical focus on the mechanisms of dehumanization and fear maximization directed at individuals of color. This was complemented by studies that explored the role of implicit bias in teachers’ evaluation, nuances in recommendation letters, and underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority populations across various academic fields. These studies and critical analyses provide a more updated understanding of the scope of implicit racial bias in education, underscoring the urgency for the sector to take meaningful actions.

Implicit Bias in Education: 2019

Implicit Bias in Education: 2019While there has been an increase in racial and ethnic diversity within the United States, many still live in segregated communities (Logan, 2013). The connection between housing and education segregation further perpetuates inequality from early life through adulthood (Wells et al., 2016). The lack of resources in schools from impoverished and segregated districts exacerbates this vicious cycle of inequality (Rothstein, 2013; Wells et al., 2016). A study by McCardle and Bliss (2019) explored the connection between school segregation and implicit bias, revealing a significant correlation between one’s personal diversity experiences and their levels of implicit bias. Specifically, individuals with more diverse experiences demonstrated lower levels of implicit bias. The complex interplay between implicit bias and education settings served as a focus of burgeoning research, drawing academic attention from 2019 to the manifestation of implicit bias in multiple educational environments, including early childhood, higher education, and special education. In the following section, we will examine publications from 2019 that explore implicit bias in each of these environments.

Early Childhood Education

Shifting our focus to the foundational years, Perszyk and colleagues (2019) aimed to investigate the interplay between racial and gender biases in young children. Considerable evidence indicated that adults tend to evaluate Black men more negatively compared to Black women, White men, and White women (Kang & Bodenhausen, 2015; Navarrete et al., 2010; Purdie‐Vaughns & Eibach, 2008; Sidanius & Veniegas, 2000). This intersectional pattern was also evident in adults’ assessments of Black boys (Todd et al., 2016). Specifically, prior research observed that preschool teachers tend to direct their visual attention in a way that suggests they anticipate disruptions from Black boys more than from other racial and gender groups of children (Gilliam et al., 2016). Building upon this foundation, Perszyk et al. focused on preschool-aged children to investigate whether this intersectional bias pattern exists within young children. Utilizing both implicit and explicit measures, the researchers evaluated how 4-year-old children responded to images of children varying in both race (Black and White) and gender (male and female). The results revealed a consistent pro-White bias among children. Furthermore, implicit bias in children was also assessed in racially more homogeneous countries. Qian et al. (2019a) conducted their research to assess the developmental course of implicit bias in Chinese participants. Their study showed that children as young as four years old displayed implicit racial bias towards outgroup members. Setoh et al. (2019) conducted research into the correlation between racial categorization and implicit racial bias in Chinese and Indian preschool children. The study revealed that children’s capacity to classify faces by race was connected to their implicit racial bias, rather than their explicit racial bias. This implied that children’s subconscious racial bias is linked to their perceptual abilities, rather than their conscious convictions about race. Additionally, the study explicitly considered the assertion that actively teaching children about racial categories might actually increase the prominence of these categories and have unintended consequences.

Special Education

One article in our sample expanded the scope of implicit biases into special education. Building on prior research by Redfield and Kraft (2012), Oelrich (2012), and Fabelo et al. (2011), Dustin Rynders (2019) conducted an in-depth critical exploration of racial disparities in identification, discipline, service, and placement associated with special education. The author’s analyses highlighted evidence that Black students are disproportionately overrepresented in the more subjective disabilities categories such as having emotional disturbance and have a higher chance of being placed in restrictive settings (e.g., a separate, self-contained class; Redfield & Kraft, 2012). Furthermore, it was also found that White teachers refer a disproportionately high number of minority students to special education (Oelrich, 2012). These decisions could adversely affect minority students, given a previous report indicating that nearly 75 percent of special education students have faced suspension or expulsion at least once (Fabelo et al., 2011). Rynders identified implicit bias as one of the contributing reasons for these disparities.

Higher Education