State of the Science: Implicit Bias in Healthcare 2018-2020

State of the Science: Implicit Bias in Healthcare 2018-2020As a pervasive influence that affects social interactions across various domains, implicit bias has drawn substantial attention in healthcare research. Questions like why youth of certain racial and ethnic backgrounds more likely to be diagnosed with disruptive behaviors (Fadus et al., 2020), or why Black individuals assumed to have stronger pain tolerance than their White counterparts (Miller et al., 2020) are just a few of the questions addressed from implicit racial bias research. Whether positive or negative in valence, implicit racial bias for or against a group influences medical providers across all specialties and negatively impacts patient care (Cooper et al., 2012; Haider et al., 2011). Between 2013 and 2017 the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity published a series of reports of implicit bias literature that analyzed the scientific foundations and impacts of implicit racial bias within the healthcare system. These State of the Science reports chronicled numerous studies that documented alarming racial disparities that result from implicit biases held at both individual and institutional levels. Specifically, Kirwan’s analysis brought together empirical research illustrating the impact of implicit bias across multiple foci in healthcare, including clinical decision-making and medical education. The report series also underscored the need for further exploration of how implicit bias manifests itself and for interventions aimed at achieving equitable healthcare outcomes. This current report updates the state of science on implicit bias in the healthcare industry across three years: 2018, 2019, and 2020. Kirwan’s first implicit bias publication, State of the Science: Implicit Bias Review 2013, laid the groundwork for our subsequent reports by evaluating implicit bias in a range of professional sectors. Regarding healthcare, both the 2013 and 2014 State of the Science reports aggregated clear empirical evidence connecting implicit racial biases with racially disparate treatment decisions across various health conditions – ranging from acute coronary syndrome to HIV (Moskowitz et al., 2012; Stone & Moskowitz, 2011). Moreover, physician biases in both doctor-patient interactions and pain assessments were documented (Burgess et al., 2014; Chae et al., 2014; Sabin et al., 2009). The State of the Science reports from 2015, 2016, and 2017 added a new dimension of analysis: the role of medical schools. These three reports shared cumulative evidence from multiple studies (Gonzalez et al., 2014; White & Stubblefield-Tave, 2017; Zestcott et al., 2016), presenting a plethora of bias mitigation strategies focused on improving equitable decision-making by medical students and ultimately reducing healthcare disparities in clinical practice. These strategies, which addressed curriculum design at the institutional level and techniques like mindfulness meditation at the individual level, provided a framework for mitigating the effects of implicit bias during the early stages of a provider’s career.

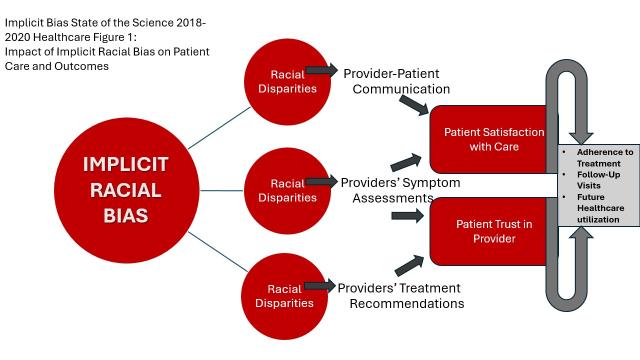

Since the publication of the landmark report, “Unequal Treatment” (Nelson, 2002), racial and ethnic treatment disparities are now one of the most widely examined topics in the field of healthcare. Three types of healthcare interactions have been consistently identified to contribute to differential treatments of patients based on race/ethnicity: provider-patient communication (see Burgess et al., 2019; Hagiwara et al., 2020; Lowe et al., 2020b), providers’ symptom assessments (see Fadus et al., 2020), and providers’ treatment recommendations (see Burgess et al., 2019; Hymel et al., 2018; Thomas, 2018). Figure 1 illustrates a series of patterns that have been observed across these dimensions. First, multiple reviews have documented that healthcare providers’ implicit biases negatively affect provider-patient communication dynamics, which in turn, can lead to lower levels of patient satisfaction with care and reduced trust in their provider (Miller et al., 2020). Patient satisfaction and trust in their provider are also well-established predictors of patients’ health-related behaviors such as adherence to treatment, follow-up visits, and future healthcare utilization (Stewart et al., 2013; Street et al., 2009). Second, suboptimal assessments of symptoms were also identified as a contributing factor to health disparities among racial and ethnic minority patients (Fadus et al., 2019; Hymel et al., 2018; Thomas, 2018). Last but not least, healthcare provider implicit bias is also associated with suboptimal treatment recommendations for racial and ethnic minority patients as compared to their White counterparts (Fadus et al., 2020; Hagiwara et al., 2020; Hymel et al., 2018; Thomas, 2018). In a similar vein, a non-trivial number of articles across the three-year period focused on the impact of implicit racial bias on patients under the age of 18, typically called pediatric patients (Fadus et al., 2020; Goodwin, 2018; Hymel et al., 2018; Johnson, 2020; Miller et al., 2020). Findings across this period revealed substantive similarities in the role of implicit racial bias between adult or pediatric cases, suggesting two important ramifications. First, such findings underscore the ongoing vulnerability of children of color in our healthcare system. Second, and perhaps even more troubling, negative childhood medical experiences may shape patients’ willingness to seek medical care later as adults (Pate et al., 1996), creating particularly challenging conditions for improving either healthy outcomes for patients themselves at the micro level or broader community health outcomes like rates of type II diabetes or infectious disease vaccination at the macro level.

In the current review, we follow the 2017 review by exploring and consolidating the research related to implicit racial bias in healthcare published between January of 2018 and December of 2020. For this industry-specific report we analyzed a total of 61 academic articles published between 2018-2020 in peer-reviewed journals. This number includes 18 published in 2018; 17 published in 2019, and 26 published in 2020. For more information about how we selected and analyzed articles, please go to our implicit bias introduction. Table 1 illustrates the variety of specialties covered across the time period. A clear variation exists with several specialties having more scholarship published in the arena than others; some specialties remain under- or unrepresented completely.

Table 1. Specialty Representation by Year 2018-2020*

*Specialties listed in alphabetical order; some articles fit multiple categories (e.g., pediatric psychiatry, surgical education)

**While COVID19 is not a formal category, we include it in anticipation of readers’ questions about the impact of the global pandemic on our analysis.

Specialty | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dentistry |

| 1 |

| 1 |

Emergency Medicine |

|

|

| 1 |

Family Medicine |

| 1 |

| 1 |

Medical Education | 5 | 8 | 7 | 20 |

Mental Health (Psychiatry & Psychology) | 3 |

| 1 | 4 |

Miscellaneous General Articles | 4 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

Neurology |

|

| 2 | 2 |

Nursing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

Obstetrics | 3 |

| 2 | 5 |

Oncology |

|

| 2 | 2 |

Otolaryngology |

| 1 |

| 1 |

Pediatrics | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

Radiology |

|

| 1 | 1 |

Surgery (all specialties) | 1 | 2 |

| 3 |

**COVID19 |

|

| 4 | 4 |

Especially relevant for this report, although both nurses and physicians work in challenging and high-stress environments that are conducive for implicit bias activation, researchers have raised concerns that current research on implicit bias in healthcare almost exclusively focuses on physician-patient interactions, which leaves a gap for further research on nurse- and/or medical staff-patient interactions (Crandlemire, 2020; Greene et al., 2018; Schultz & Baker, 2017). We therefore attend to the broader category of “healthcare provider” in this report to encompass practicing physicians, nurses, medical staff, interns and residents.

Understanding where the science has led scholars to date is an essential stimulus for further study. Our goal is to offer an accessible summary of implicit bias research in healthcare during this three-year window and to present insights for potential future research directions, including the development of effective interventions that contribute to the ultimate goal of establishing a more equitable healthcare system for all.